Lilia Facio Hernández offers us one of the 37 gorgeous varieties of cakes made at the Museo del Dulce de la Calle Real (the Royal Road Candy Museum). Buy as little as a slice to indulge yourself, or purchase as much as an entire cake for a party dessert. Each cake is more beautiful than the next and each one has a name from Mexico's history. This one is the Iturbide, named for General Agustín Iturbide, hero of Mexico's 1810 War of Independence and designer of Mexico's first flag.

Mexico Cooks! has had some very sweet interviews, but none has been sweeter than the time we spent recently with Arquitecto Gerardo Torres, owner of Morelia's Museo del Dulce (candy museum). Imagine spending several hours in a 19th Century Morelia mansion presently converted into a real-life version of Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory! Delicious aromas of melting sugar constantly waft through the air, sepia-tone photographs carry us back to earlier times in Morelia, and charmingly attractive employees treat each customer like visiting royalty.

Walking into the Museo del Dulce's retail chocolate and cake shop is a voyage to the Porfiriato (the era of Porfirio Díaz), a trip to the 19th Century.

De la Calle Real, the candy-making firm that's part of the Museo del Dulce, has been in constant business since 1840. The oldest family of candy makers in Morelia prides itself on the continuity of its passion for the sweet life. Family recipes, hand-written in spidery script on yellowing pages, family photographs dating over the last two centuries, and the importance of family heritage glow in every corner of the building that was at one time the Torres home. Every corner of the many rooms of the house, now converted to a museum and retail shop, breathes history and love of Mexico.

An old wooden carreta (cart) parked in one of the museum patios looks like it's just waiting to be hitched up to a team of draft animals.

The original De la Calle Real candy shop was located in Morelia's portales (arched, covered walkways) on Avenida Madero, across from the Cathedral. Later, the shop moved to its current spot–still on Avenida Madero, just a few blocks to the east. Now, De la Calle Real has locations in Morelia's upscale Plaza Fiesta Camelinas, in Mexico City's traditional neighborhood Coyoacán, and will soon open branches in both Sanborns and Palacio de Hierro, two of Mexico's swankiest department stores.

One room of the museum is set up with machinery used in the 1940s, when the family candy business was only 100 years old! This beautiful hand-made copper pot has a double bottom, like a bain-marie, to keep the cooking candy from burning.

Not only does the company continue to produce candy from old family recipes, Arq. Torres also prides himself on participating in the rescue of recipes dating back as far as pre-Colonial days. Sweets composed of native fruits and vegetables were made with honey until the Spanish brought sugar cane to the New World. Chocolate, native to Mexico, was consumed only by the indigenous nobility as an unsweetened cold drink–served either as bitter chocolate or flavored with chile–prior to the arrival of the Spanish.

Decorated like a convent shop, this museum and sales room carry us back to the time when fine candies were made in Morelia by cloistered Dominican nuns. Click on the picture to enlarge any photo.

In the demonstration kitchen, Mexico Cooks! watched as the cook combined equal parts fresh membrillo (quince) pulp and cane sugar in a copper pot. She was preparing ate de membrillo (quince candy). When the mixture formed una cortina (a curtain) without dripping as the wooden spoon was lifted from the pot, the ate was at its point of perfection.

It's an easy walk from the Centro Histórico (Morelia's historic center) to the Museo del Dulce, but why not take the little tourist trolley instead? Hop on in front of the Cathedral (buy tickets at the Department of Tourism kiosk in the Plaza de Armas, just to the right of the Cathedral). The trolley will take you from there to some of the most important historic sites in Morelia, including the Santuario de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, the Conservatorio de las Rosas (the oldest music conservatory in the New World) and the glorious Templo de las Rosas (Church of St. Rose of Lima, originally the home of Morelia's 16th Century Domincan nuns), and the Museo del Dulce. The trolley trip, which lasts slightly over an hour, gives the tourist plenty of time to enjoy all of these Morelia traditions.

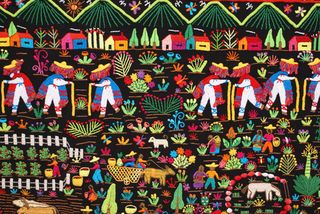

Dulces de la Calle Real (the candy maker's brand name) prepares specialty ates de membrillo in molds which create the embossed images of some of Morelia's historic landmarks: (from left) Las Tarascas fountain, the 18th Century aqueduct, and the Cathedral.

The candy maker prepares and packages small gourmet ates made of strawberry, pineapple, blackberry, and other fruits that are little-used in this presentation. Each box tells a story, each ate is perfectly molded.

For special culinary events, the museum occasionally re-creates antique recipes, some of which date to Mexico's colonial days. This just-made historic ate contains chayote (vegetable pear, or mirleton) and fresh fig leaves.

An excellent video, shown for everyone visiting the Museo del Dulce, tracks the history of candy making in Morelia. Long known for ates (fruit pastes) and laminillas (fruit leathers), Morelia developed another culture of candies during the Porfiriato, the long presidency of Porfirio Díaz (1875-1910). During those 35 years, the influence of everything French invaded Mexico and colored the fashion of Mexico's upper-class society. French-style sweets became all the rage, and Morelia never lagged in preparing candies and cakes to meet the demand. Today, Porfiriato-style cakes, beautiful to see and delicious to taste, are made and sold by De la Calle Real. You can sit for a while in the cozy elegance of the Café del Patio de Atrás (the Back Patio) coffee shop and choose from a menu of 37 different cakes, house-made Mexican hot chocolate, delicious fresh-made ice creams, and a mind-boggling selection of other delights from the Museo del Dulce's menu.

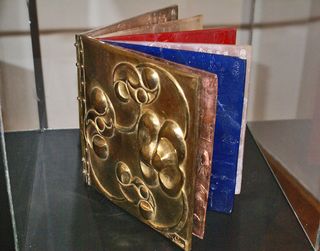

The candy maker created beautiful embossed jamoncillo (milk candy similar to penuche) ovals to honor Mexico's 2010 Bicentennial. Each one carries the image of a hero of Mexico's independence. These candies represent Miguel Hidalgo, father of the Independence. The candy molds are hand-carved by a museum employee.

There's a room of the store where you can dress up in Victorian-era clothing–from elegant feathered hats to fancy silk dresses, from black top hats to cutaway suits–and a shop employee will take your picture. What a terrific souvenir!

In part of the retail shop, lines of baskets hold individual candies for instant gratification of your sweet tooth–or to pack easily into your suitcase to carry home as gifts. The tissue-paper-wrapped candies are similar to jamoncillo.

Another entire room of the store is just stuffed with a variety of small toys, perfect for an inexpensive souvenir from Morelia. Inexpensive and easy to pack, they're exactly right for the child in all of us. These are baleros. The idea is to hold the long handle in your fist (with the cup on top) and catch the small wooden ball. It looks easy to accomplish–but it's quite a challenge!

Nuns originated Mexico's famously delicious rompope (a kind of eggnog). You'll find it in several flavors and bottles ranging from small to large, all made by the artisan candy makers at Dulces de la Calle Real.

Absolutely everything about the Museo del Dulce and De la Calle Real is devoted to reverence for the past, passion for perfection in the present, and devotion to the future preservation of Mexico's traditions. Every product and its packaging, designed and developed by Arq. Torres, is an homage to Mexico. Each candy box incorporates an old photo and a paragraph-long history lesson, with the treat you purchased as your sweet reward for learning.

Elia Ramírez Ramírez is packing small sweet treasures in Mexican pottery containers. The packaged candies are destined for the retail store. All employees who work directly with the public wear 19th Century costumes.

As Arq. Torres said during our time together, "We are the in-between generation. We still remember mothers and grandmothers who made candy at home. We still hold that tradition in our hearts. It's up to us to keep those memories alive, to pass them to our children and help them pass the traditions to the generations that follow. Otherwise, we will forget everything that truly makes us who we are."

Arquitecto Gerardo Torres, the delightful gentleman who runs this sweet business with passionate care, comes from a long line of candy makers. He showed Mexico Cooks! lovely old photos of his mother, his grandmother, and his great-grandmother–candy makers one and all.

Whether you are a fan of jamoncillo, ate, chocolate,

rompope or another traditional Mexican sweet, you will be as

thrilled as Mexico Cooks! was with everything about the Museo del Dulce

and De la Calle Real. If De la Calle Real is your first experience of

heavenly Mexican candy, it will spoil you for every other kind.

Come to visit, stay to give in to temptation! Employees at the Dulces de la Calle Real Museo del Dulce will be glad to help you find the perfect house-made candy for yourself, your relatives, and your friends.

De la Calle Real Museo del Dulce

Av. Madero #440

Colonia Centro

Morelia, Michoacán, México

443.312.8157

Looking

for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click

here: Tours.