In this mural around the corner from the restaurant, the silver Twinkie, icon of the Pinche Gringo BBQ joint, floats above Mexico City's Palacio de Bellas Artes (Palace of Fine Arts), offering a bilingual welcome to everyone in the Distrito Federal who wants Texas-style barbecue. You might be amazed to see how many people line up every day for a pile of smokey pork meat and a couple of sides or a mile-high beef brisket sandwich. In just seven months, this BBQ heaven has had to expand twice to accommodate the crowds. G'wan, line up. We did. Photos by Mexico Cooks! unless otherwise noted.

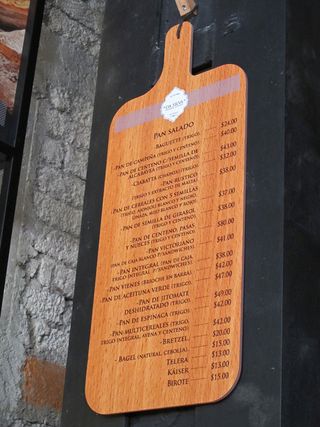

Pinche Gringo BBQ menu. Click on any photo to enlarge the image. Photo courtesy Pinche Gringo.

Mexico Cooks!, a person of a certain age, usually manages a fair degree of decorum when in public. "Pinche" is not a very nice word in Mexico, especially when attached to gringo, a word I certainly know but refuse to use either in writing or speaking. It surprises me no end when foreigners who hail from north of the Mexican border identify themselves with the derogatory term gringos, but Dan Defossey, the pinche gringo himself and founder of the feast, brings it off with grace.

Dan is a native New Yorker, transplanted to Austin, Texas and thence to Mexico City. He's a righteous smoked barbecue fiend. When he arrived in Mexico's capital, he had plenty of barbecue eating experience but no restaurant-running experience. It was the barbecue-eating experience he missed during his first four years in Mexico. Until his Pinche Gringo BBQ joint hit the scene in Colonia Narvarte, having a taste of 'cue meant an 11-hour drive to the Texas border.

Dan retrofitted the silver Twinkie, otherwise known as an Airstream travel trailer, for use as a cafeteria-style restaurant counter. Line up, study the wall-mounted menu while you wait, grab a tray and tell the genial (and bilingual) staff inside the trailer what you want to eat. A plated meat order (using the term loosely, since the Pinche Gringo piles your meat not on a plate but on a big sheet of paper on your tray) comes with two sides; you can order sides separately if you choose a sandwich. My order? "Carne de cerdo deshebrado (de-seh-BRAH-doh, Texas-style pulled pork), macaroni and cheese, and barbecue beans, please." My wife had ordered the pork ribs, with sides of potato salad and cole slaw; the plan was to share everything.

The line forms at the rear. The day Mexico Cooks! and a couple of boon companions went to eat BBQ, we purposely went quite early (1:00PM) to avoid a long wait. Mexico eats its main meal of the day at around three o'clock and we wanted to beat the rush. It turned out to be a strangely slow day; when there's a crowd, the line can snake all the way to the front door, down a step, and around the corner to the end of the building. Note the picnic table: at this very rustic restaurant, all seating is this type.

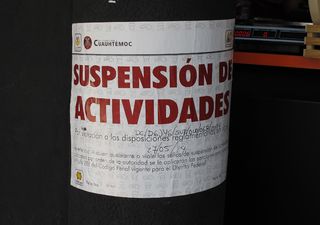

Pinche Gringo accepts cash payments and all credit cards. You can also pay via the PG iPad at the cashier–using PayPal Check-In, which takes the cost of your meal directly out of your PayPal account. It's a neat new wrinkle in payment processing. From the top down, the sign translates to, "Really damn practical, really damn easy, really damn fast!"

Time to cut to the chase: these are the pork ribs, a half-rack of smoked ribs, thickly drizzled with PG sauce and accommpanied by potato salad, cole slaw, a sesame-seeded roll, and Texas sweet tea. The flavor of the ribs was soft and smokey, but our companions, who also ordered ribs, said they weren't as fall-off-the-bone tender as he has eaten them the other four times he's been to Pinche Gringo. "Why did I pick the ribs? I love the pulled pork best," he regretted.

My other companion's potato salad tasted just like Mom used to make: rich with mayonnaise, slightly mustard-y, and just the right combo of tang and potato. The texture was strange to me, almost like mashed potato with lumps. I prefer my potato salad chunky, with the potatoes at a melt-in-the-mouth tenderness. The cole slaw, made with purple cabbage and carrots, was perfect.

The big pile-on-the-tray of pulled pork, sauced and with a side of mac'n'cheese and another of barbecue style beans. The fork-tender, slightly fatty pulled pork was the hands-down winner of the meal. I was loathe to share this pile with a companion in exchange for some of her ribs, but a deal is a deal.

The Texas-style beans were just right, sweet and smoky. The mac'n'cheese was slightly spicy, very cheesy, and creamy in the mouth. Score!

Smoked, tender beef brisket, chopped, stacked up six inches high and oozing out of the confines of its bun, served with onion and dill pickles and of course the standard PG sauce. A generous customer let me take this picture of his meal–but I noticed that he didn't offer me a taste. Some people just want it all for themselves!

Luis Urrutia Alonzo, one of the PGBB staff, let me sneak behind the scenes to photograph the four-door wood-fired gargantuan smoker. At the bottom left corner you can see the little burner. Gauges indicate that the heat is kept at a slow, even temperature. The meat is cooked for a while to seal in the juices, then wrapped in aluminum foil and smoked for ten hours–overnight. Dan Defossey brought the smoker from Texas, along with the elderly Airstream trailer. Sometime when you're at Pinche Gringo, ask him to tell you the tale of the trip.

Two of the several drink options: barrels of free-refill lemonade and Texas sweet tea. In addition, there's a good range of soft drinks and several kinds of beer.

Pie for dessert! The pies change every month. The pies for July, in this case: on the left, raspberry and cheese. On the right, real down-home apple pie. Which to choose! We all had the apple; it was as good as any I've ever had–really good.

So long for now, Pinche Gringo! We'll see you again soon to try more of your smokey Texas menu. You're a welcome addition to the Mexico City restaurant scene. Even though you don't offer tortillas or micheladas or Mexican salsas, everybody loves your style.

Pinche Gringo BBQ

Cumbres de Maltrata 360

Colonia Narvarte

Del. Benito Juárez 03020

Ciudad de México, Distrito Federal

Tel. 55 6389 1129

Hours: Wednesday, Thursday, Friday: 1PM – 7PM

Friday, Saturday, Sunday: Noon – 7PM

Monday and Tuesday: Closed

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.