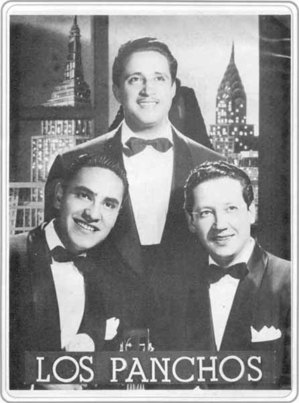

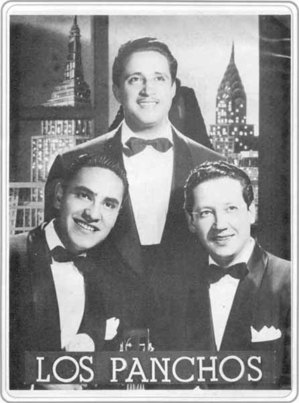

Trio Los Panchos, from the 1950s. They’re still playing today and everyone of every age in Mexico knows all the words to all the songs they’ve sung since their beginning. You can hear them here: Los Panchos

A few nights ago some friends and I were having dinner at a local restaurant. A wonderful trio (lead guitar, second guitar, and bass) played a broad

selection of Mexico’s favorite tunes while we enjoyed our

food and conversation. From the table behind us, a woman’s voice rang

out in English, "Boy, these mariachis are really good."

Her comment, one I’ve heard over and over again, made me think about

the many varieties of Mexican music. Not all Mexican music is mariachi, although many people assume that it is.

It’s just as incorrect to classify all Mexican music as mariachi as it is to classify all music from the United States as jazz. Mariachi has its traditions, its place, and its beauties, but there are many other styles of Mexican music to enjoy.

Ranchera, norteña, trio, bolero, banda, huasteco, huapango, trova, danzón, vals, cumbia, jarocho, salsa, son–??the list could go on and on. While many styles of music are featured in specific areas, others, like norteña, banda, ranchera, and bolero,

are heard everywhere in Mexico. Let’s take a look at just a few of the

most popular styles of music heard in present-day Mexico.

Norteña

Música norteña (northern music) will set your feet a-tapping and will remind you of a jolly polka. Norteña

had its beginnings along the Texas-Mexico border. It owes its unique

quality to the instrument at its heart, the accordion. The accordion

was introduced into either far southeastern Texas or the far north of

Mexico by immigrants from Germany, Czechoslovakia, or Poland. No one

knows for sure who brought the accordion, but by the 1950s this

rollicking music had become one of the far and away favorite music

styles of Mexico.

A norteña group of musicians playing a set

of trap drums, a stand-up bass, and the accordion produces an instantly

recognizable and completely infectious sound. The songs have a clean,

spare accordion treble and a staccato effect from the drum, while the

bass pounds out the deep bottom line of the music.

Norteña is popular everywhere in Mexico. Here in Guadalajara, conjuntos norteños

(bands) often play as itinerant musicians. These are the musicians who

are often hired to play serenades in the wee hours of Mother’s Day

morning, who play under the window of a romantic young man’s girl

friend while she peeps from behind the curtain, and who wander through restaurantes campestres (country-style restaurants) all over Mexico to play a song or two for

hire at your table.

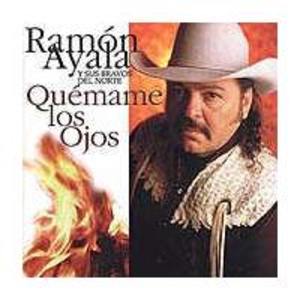

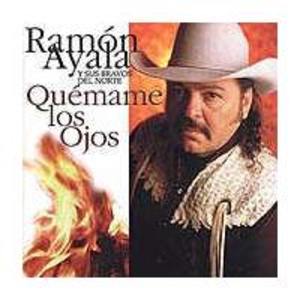

The undisputed king of música norteña is Ramón Ayala. Over the past 30 years he has recorded an amazing 75 albums. His current group, Los Bravos del Norte,

is heard everywhere, ??on every radio station and every jukebox. The group

is widely imitated but never superseded. Ayala turns out well-crafted

and balanced music, featuring lyrics with universally understood human

themes. The songs, like the majority of norteñas, are

about tragedy, loneliness, broken relationships, almost unbearable

longing and pain, and about experiencing love in all its complicated

nuances. You can listen to Ramón Ayala and sus Bravos del Norte: Ramón Ayala

Banda de Viento and Banda

Banda de viento and banda are similar musical styles:

both have a military legacy. Each has moved in its own direction to

provide different types of entertainment.

In Zacatecas, the state banda de viento plays concerts day and night.

Banda de viento (wind band, or brass band) originated in

Mexico in the middle 1800s during the reign of Emperor Maximilian and

Empress Carlota. Later, Presidents Benito Juárez and Porfirio Díaz

commissioned the creation of brass bands in their home state, Oaxaca,

in imitation of the brass bands that entertained at the Emperor’s

court.

The huge upsurge of popularity of brass bands in Mexico came in the

early 20th Century. After the Mexican revolution, local authorities

formed "Sunday bands" made up of military musicians who played in

municipalities’ plaza bandstands all over Mexico.

The Banda del Estado de Zacatecas (Zacatecas State Band) plays: Marcha de Zacatecas (Zacatecas March)

There are regional differences in banda de viento

style, but you can still take a Sunday stroll around many rural Mexican

plazas as the tuba oompahs the bass part, the trumpets blare, squeaky

clarinets take the lead, and the tamborazo (percussion) keeps

the beat. The Sunday municipal band concert no longer exists in some large cities (although you can hear weekly concerts in both Guadalajara and Zapopan),

but something new has taken its place: banda.

Banda music, which exploded onto the Mexican music scene in the 1990s, is a direct outgrowth of the municipal bands of Mexico. Banda is one of the most popular styles of dance music among Mexican young people. In small towns, we’re often treated to a banda group playing for a weekend dance on the plaza or at a salón de eventos

(events pavilion) in the center of the village. The music is inevitably

loud, with a strong bass beat. You’ll hear any number of rhythms, from

traditional to those taken from foreign music. It’s almost rock and

roll. It’s almost–??well, it’s almost a lot of styles, but it’s pure banda.

Few expatriates go to these dances and that’s a shame, because it’s

great fun to go and watch the kids dance. You might want to take

earplugs; the banks of speakers can be enormous and powerful.

The dancing will amaze you. Children, teenagers, and adults of all ages dance in styles ranging from old fuddy-duddy to la quebradita. La quebradita

is a semi-scandalous style of dance which involves the man wrapping his

arms completely around the woman while he puts his right leg between

her two as they alternate feet and twirl around the dance floor.

Complete with lots of dipping and other strenuous moves, la quebradita is a dance that’s at once athletic and extremely sexual.

Bolero

In the United States and Canada, it’s very common for those of us who are older to swoon over what we know as the ‘standards’. Deep Purple, Red Sails in the Sunset, Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,

and almost anything by Ol’ Blue Eyes can take us right back to our

youthful romances. Most of us can dance and sing along with every note

and word.

Here in Mexico, it’s the same for folks of every age. The romantic songs from the 1940s, 50s, and 60s are known as boleros. The theme of the bolero

is love–??happy love, unhappy love, unrequited love, indifference, ??but

always love. I think just about everyone has heard the classic Bésame Mucho, a bolero written

by Guadalajara native Consuelo Velásquez. This timeless favorite has

been recorded by Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, and The Beatles, among

countless other interpreters of romance.

Here’s Luis Miguel, one of Mexico’s modern interpreters of bolero, singing Sabor a Mi: Luis Miguel

Armando

Manzanero, born in 1935 in Mérida, Mexico, is one of the most famous writers of bolero. His more than 400 songs have

been translated into numerous languages. More than 50 of his songs have

gained international recognition. Remember Perry Como singing It’s Impossible? The original song ??by Armando Manzanero ??is called Somos Novios.

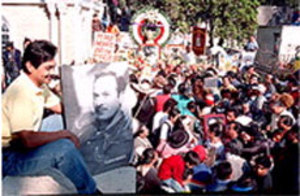

Crowds memorialize Pedro Infante, one of Mexico’s greatest stars.

Agustín Lara was another of Mexico’s prolific songwriters. Before Lara

died in 1973, he wrote more than 700 romantic songs. Some of those were

translated into English and sung by North of the Border favorites Bing

Crosby, Frank Sinatra, and yes, even Elvis Presley. The most famous of

his songs to be translated into English included You Belong to My Heart (originally Solamente Una Vez), Be Mine Tonight (originally Noche de Ronda), and The Nearness of You.

Ranchera

The dramatic ranchera (country

music), which emerged during the Mexican Revolution, is considered by

many to be the country’s quintessential popular music genre. Sung to

different beats, including the waltz and the bolero, its lyrics traditionally celebrate rural life, talk about unrequited love and tell of the struggles of Mexico’s Everyman.

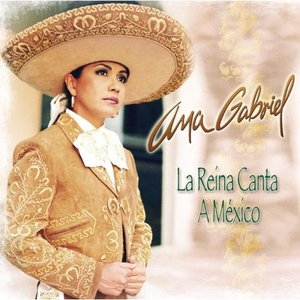

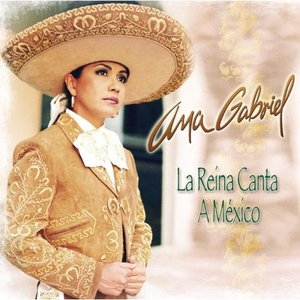

Ana Gabriel is today’s reigning queen of música ranchera. Listen to her sing one of her all-time great songs: Y Aquí Estoy

Ranchera finds its inspiration in the traditional music that

accompanies folkloric dancing in Mexico. Its form is romantic and its

lyrics almost always tell a story, the kind of story we’re used to in

old-time country music in the United States: she stole my heart, she

stole my truck, I wish I’d never met her, but I sure do love that gal.

Pedro Infante, Mexico’s most prolific male film star, is strongly associated with the ranchera

style of Mexican music. One of the original singing cowboys, Infante’s

films continue to be re-issued both on tape and on DVD and his

popularity in Mexico is as strong as it was in his heyday, the 1940s.

Infante, who died in an airplane accident in 1957 when he was not quite

forty, continues to be revered and is an enormous influence on Mexican

popular culture.

Ranchera continues to be an overwhelmingly emotional favorite

today; at any concert, most fans are able to sing along with every

song. This marvelous music is truly the representation of the soul of

Mexico, the symbol of a nation.

Ana Gabriel is the queen, but Vicente Fernández is the king of ranchera.

Listen to him sing one of his classics: Por Tu Maldito Amor

Vicente Fernández, whose ranch, huge restaurant, and large charro-goods store are located between the Guadalajara airport and Lake Chapala, is the current reigning king of ranchera–??indeed, he is considered to be the King of Mexico.

Mariachi

Mariachi really is the music that most folks think of when they think of Mexico’s music. Mariachi originated here, it’s most famous here, and it’s most loved here. The love of mariachi has spread all over the world as non-Mexicans hear its joyous (and sometimes tragic) sounds. At this year’s Encuentro Internacional del Mariachi (International Mariachi Festival) in Guadalajara, mariachis

from France, Czechoslovakia, Canada, Switzerland and the United States

(among others) played along with their Mexican counterparts.

In the complete mariachi group today there are six to eight

violins, two or three trumpets and a guitar, all standard European

instruments. There is also a higher-pitched, round-backed guitar called

the vihuela, which, when strummed in the traditional manner gives the mariachi its typical rhythmic vitality. You’ll also see a deep-voiced guitar called the guitarrón which

serves as the bass of the ensemble. Sometimes you’ll see a Mexican folk harp,

which usually doubles the base line but also ornaments the melody.

While these three instruments have European origins, in their present

form they are strictly Mexican.

Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán is the most famous mariachi in the world. Every year in Guadalajara they honor us with their presence at the Encuentro Internacional de Mariachi. If you’ll be in the city August 31 through September 9, 2007, plan to attend one of the nightly Galas de Mariachi at the Teatro Degollado. It’s an unforgettable experience. Listen to them now: Entra en mi Vida

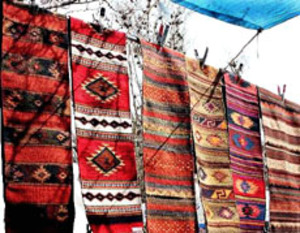

The combined sound of these instruments makes the music unique. Like the serape

(a type of long, brightly striped shawl worn mainly by Mexican men) in

which widely contrasting colors are woven side by side–??green and

orange, red, yellow and blue–the mariachi use sharply contrasting

sounds: the sweet sounds of the violins against the brilliance of the

trumpets, and the deep sound of the guitarrón against the crisp, high voice of the vihuela; and the frequent shifting between syncopation and on-beat rhythm. The resulting sound is the heart and soul of Mexico.

Next time you go to your local music store, look on the racks of CDs

for some of the artists and styles of Mexican music I’ve mentioned. You

may be quite surprised to see how popular the different styles are in

the United States and Canada. As the population of countries North of

the Border becomes more Mexican, the many sounds of Mexican music

follow the fans. Next thing you know, you’ll be dancing la quebradita.