Fiestas! A Mexican town goes all-out for its fiestas. Every barrio (neighborhood) celebrates its special saint. Any specialty item produced in a town gets at least a couple of days’ party: the paleta in Tocumbo, a cheese in Cotija, maque (laquerware) in Uruapan. El Día de los Muertos (the Day of the Dead), Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe), Candelaria (Candlemas)–each merits a party. But the biggest, most whoop-de-do wonderful fiesta time of the

year comes to one small town near Guadalajara at the end of November. Starting on the evening of November 22

and culminating on the night of November 30, the town celebrates the

fiestas of its patron saint, San Andrés (St. Andrew).

Dare we go up on the ferris wheel? It’s called rueda de la fortuna (wheel of fortune) at the fiestas in this town.

Each day of the fiesta is sponsored by a different worker’s group, or gremio. For example, there are gremios for the masons, gardeners and domestic workers, plumbers and electricians. One day of the yearly fiestas patronales is sponsored by a large local hotel, and another is sponsored by los hijos ausentes,

(the absent children), those who were born and raised in the town but who

now live in the United States or other parts of Mexico.

In the pre-dawn hours of every morning, the angels are awakened (so goes a local saying) by hundreds of booming cohetes

(skyrockets) set off in the church atrium. Soon after, pealing

church bells call the faithful to 6:00 AM Mass, along with oom-pah bands

of musicians processing through the cobbled streets leading the

procession to the church of San Andrés. Thousands more skyrockets

thunder to the heavens throughout the day and night, every day and night.

Cohetes courtesy of a terrific photographer, Flickr user joven_60. Thanks, David, you captured everything but the booms!

The faint of heart leave town for the duration, dogs bark,

cats hide, but the tiniest babies yawn and cuddle closer to their

mothers as they sleep undisturbed through all of the racket. Last year,

on the day that was sponsored by the gremio de los albañiles (construction workers), 7,000 thundering skyrockets were set off in one 24-hour period. You read that right, seven thousand. Nearly 300 an hour for 24 hours!

Pozole (a pork, corn, and chile stew) and atole (a hot drink, in this case made of corn) warm you inside and out during the fiestas in Mexico’s chilly winter.

Each gremio sponsors a second procession and

celebration of Mass at 7:00 PM every evening and then the fun begins. The

fiestas are part religious observance, part circus sideshow, part food

festival, part carnival, part dance party, part courtship, and part

competition. You’ll find every sort of food being served on the plaza.

There are in-season guasanas (fresh green garbanzo beans, steamed in the pod on a brazier), tacos of every description including carne asada (marinated beef), beef tongue, and tacos al pastor (pork, marinated, roasted on a spit, and chipped off to order, sizzling hot).

Hungry celebrators of any age can choose from tamales, pozole, atole,

pizza baked in a portable oven, hot dogs, hot cakes, hot corn on the

cob, hot fresh-made potato chips, hot breads and hot drinks. Hot

cinnamon tea is a specialty of the fiestas, served sweetened and, more

often than not, with a piquete (a stiff shot of tequila, rum or rompope (eggnog liquor).

The fiestas bring great friends together for great fun.

There are games of chance galore: typical ring toss games (encircle the

prize and you win it), canaries that tell your fortune, shooting

gallery games (watch out for the little stuffed monkey. Someone hits it

and it pees in an astonishingly long trajectory).

Stop at Bebidas Paraíso for a drink. Tequila, rum, brandy, whiskey–these temporary bars, set up just for the fiestas, are called terrazas.

There’s a long street of tchotchke booths, selling everything from plastic

kitchen wares to CDs to clothes to toys (Christmas is just around the

corner) to souvenirs of the fiestas. It’s easy to get lost in the vast numbers of tiny trinkets in each booth.

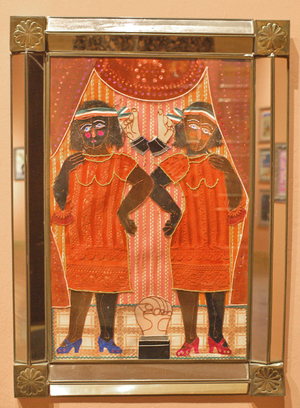

There are specialty crafts booths selling fantastic embroidery, wood

carvings, pottery, and regional candy specialties. Want to ride a big

white goat with a saddle? Hop on!

Everything is made luminous by the chilly, starry skies. The

warmth of twinkling colored lights, the sounds, the smells and the

excitement of young and old alike is palpable in the chilly night air.

The band revs up around 8:00 PM and plays con gusto till the last possible moment, frequently until two, three or four in the morning.

Coheteros (fireworks makers) spend part of each fiesta daytime setting up the evening’s castillo.

And overshadowing all of these goings-ons is the grand finale of each evening, the castillo (castle). A set-piece fireworks display made of thin strips of bamboo, wires, strings, black powder and fuses, the castillo

is mounted on a 20-foot-high 6-inch thick pole in the middle of one of

the narrowest streets in town. The miracle of engineering and

architecture has its moments of glory around 11:00 each evening. The coheteros,

the men who build these fireworks marvels, mill around their creation

all evening, having a few beers while they baby sit the ‘castle’.

At about 10:30, murmurs start running through the crowded plaza: "A qué horas se quema?" (What time will it be burned?) Suddenly, the castillo jiggles-the long fuses are loosened and shaken. It’s time! The coheteros

grin and suck their cigarettes as the music crescendos. All eyes are

fixed on the bamboo center of attention. And, whoosh, the first

long fuse is lit with the hot end of a cigarette, the sparks climb

higher, and BANG! The first wheel of the display catches fire with a

whistle, a whir, and a buzz.

Brilliantly colored flames shoot out in the form of—wait! What is that? It’s an elephant—no, wait, it’s a bull!

For mere moments the bull whirls in space, isolated in the darkness and

shooting sparks into the crowd. And then whoosh another fuse, and this

time it’s a champagne glass that bursts into the night, and then a

flower, and then spinning discs of neon green flame, and then fountains

of what look like diamonds fall into the night, showering over the

crowd.

Six little boys run merrily under the exploding castillo, protected by cardboard cartons held over their heads. Oh the risk! Oh the joy! And BANG, the castillo

erupts again, now at the higher levels—this time a guitar, and an apple

and a poinsettia flame out into the night. And at the highest level,

what’s this? A folded fan falls open, shooting flames of purple, pink,

blue, and green–no! There’s a head. It’s a peacock, twirling and

shooting fantastic cascades of sparks from the feathers of its tail.

And then the coup de grace—at the very top, a ring of brilliant fuchsia fire spins faster, faster, faster, until the corona

(crown) loosens its moorings from the structure and flies higher and

higher into the starry sky, trailing glittering sparks until finally it

burns out with a hiss that is echoed by the sigh of the crowd. The castillo is finished for tonight, the smell of smoke and gunpowder lingering in the air.

The band music takes up the slack. Families with little ones and the

old folks head home as soon as the last spark dies. The teens and the

young men and women begin their sloe-eyed walk around the plaza. In the

sidewalk cantinas, members of the sponsoring gremio

order another tequila, in food stands couples eat another taco, and then

it’s home to bed to dream of what’s been tonight and what tomorrow

might bring.

A globo (balloon) vendor plies the fiesta crowd.

And all the while they dream, the band plays, the stars

shine and the coheteros smile and tip yet another beer to toast their evening’s work.

http://pagead2.googlesyndication.com/pagead/show_ads.js