The unprepossessing doorway to UNEAMICH mfa/eronga, the Erongarícuaro, Michoacán artists' cooperative originally founded in 1981 by Steven and Marina Rosenthal. "Go to the corner where the primary school is, turn right, and go halfway down," read Marina's directions. 'Halfway down to what,' wondered Mexico Cooks!, but the building was easy to find. All photos by Mexico Cooks! except as noted.

Pátzcuaro, the original capital of Michoacán, is a well-known destination for tourists, whether they are interested in pre-Hispanic religious sites, centuries-old architecture, modern working artisans, or regional Purhépecha cuisine. Just a few minutes' drive away, another side of Michoacán exists: small-town, little-visited, and still very much oriented toward Mexico's traditional way of life. In Erongarícuaro, the day bustles gently around the small plaza. The pace is slower even than that of Pátzcuaro.

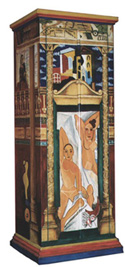

In the Erongarícuaro, Michoacán taller (workshop) of Muebles Finos Artesanales Erongarícuaro–the UNEAMICH wholesale entity branded as mfa/eronga–Marina Rosenthal stands before a custom-painted panorama of canvas nudes. You can put your own face in one of the vacant spots.

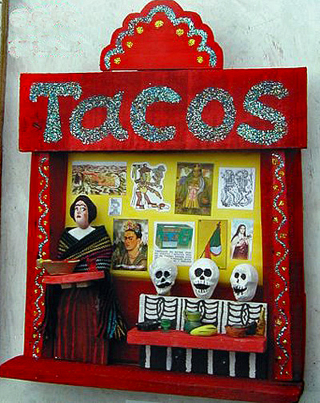

Erongarícuaro, attractive in a well-worn, frayed-cuff style, is home to about 13,000 people, including a few souls from 'away'. Europe, Canada, and the United States are equally represented. Long a bohemian outpost (according to local legend, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera and their international cohorts were frequent visitors), Erongarícuaro still attracts the slightly eccentric foreigner: a handful of people setting up a sustainable community, another handful interested in communal housing, and one or two long-time residents working in town.

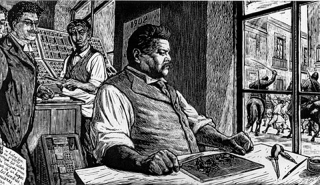

The sales and reception room at UNEAMICH mfa/eronga, where we talked with Marina. Photo courtesy Bernie Frankl, Tucson, AZ.

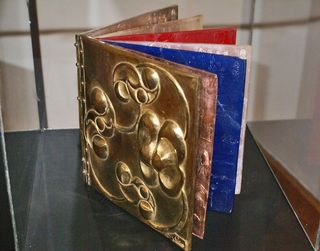

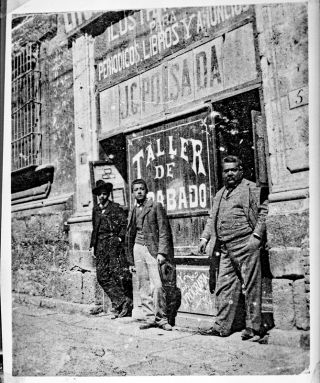

Steve and Maureen Rosenthal, originally from Arizona, have lived and worked in Erongarícuaro for nearly 50 years. Their commitment to the town and its people runs deep; they've put their lifework into training artists, producing incredibly beautiful furniture and home decoration over the course of the years. Their business, UNEAMICH mfa/eronga, has evolved from its 1980s-era origins as an Escuela Taller (Workshop School) to the worker-owned cooperative that it is today. Along the way, the Rosenthals and the artist owners have created a living heritage for Erongarícuaro.

One of the artists' workrooms at UNEAMICH mfa/eronga. Most of the 40-plus artist members of the cooperative were attending a community funeral on the day that Mexico Cooks! visited the UNEAMICH/mfa/eronga taller.

Mfa/eronga (the name of the UNEAMICH store that Steve runs in Tucson) has talleres (workshops) on both sides of its quiet Erongarícuaro street. One is the carpentry workshop for building and carving the wooden furniture; the other is filled with artists' cubicles where the fine decoration work takes place. Mexico Cooks! greeted Marina (Maureen's name loosely translated into Spanish) Rosenthal with a happy, "Finally! We've wanted to visit you for years!" We hugged and laughed that our meeting had been delayed for so long.

The carved and painted backrest of a UNEAMICH mfa/eronga chair. Click on any photo for a larger view.

While giving us a running history of the business, Marina took us on a tour of the two talleres. "Steve and I came here in 1970 to finish writing a screenplay, but the option to make the movie just never panned out. By then, we were so in love with this part of Michoacán that we didn't want to leave. We started making painted furniture, and little by little, customers started seeking us out.

The exterior and interior of one of mfa/eronga's fabulous painted pieces. Photo courtesy mfa/eronga.

"When Cuahutémoc Cárdenas was governor of Michoacán (1980-86), he was a huge supporter of the state's regional arts. You know that he was the son of Lázaro Cárdenas del Río, Mexico's forward-thinking president from 1934-1940, and he had a lot of his father's sensibilities. One of his projects was to open Escuelas Talleres–workshop schools–where artisans could receive training that would enhance the quality of their work and make it more easily sold. That's where we came in: our workshop began to receive state support for training artists. Literally dozens of artists have trained with us; some continue to work with us now, and some of our current workers are the children of those men and women who initially trained here.

Work facilities at UNEAMICH mfa/eronga are primitive, but the cooperative of artists creates glorious work in spite of the harsh conditions.

"Most of the artists we've trained knew some carving or painting techniques before they came to us. Their level of general knowledge of art was practically nil, though: none knew of the great European classical or modern painters and none had heard of any artists north of the Mexican border. Few knew of Mexico's great artists: Rivera, Kahlo, Tamayo, the Coronel brothers, and Juan O'Gorman, just to name several. One of my greatest joys has been taking our extremely talented artists to Morelia, to Guadalajara, and to Mexico City to show them art's possibilities outside their limited frame of reference.

UNEAMICH mfa/eronga artists hand-paint and hand-finish bateas (hand-carved shallow wooden bowls) from their own designs–or from your special-order design.

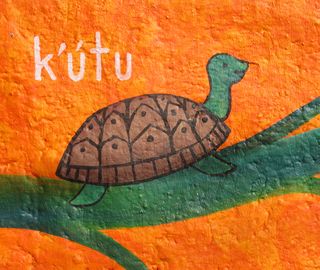

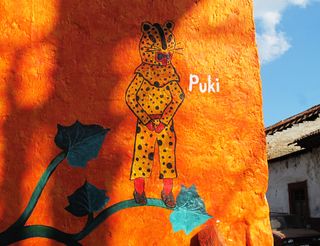

"We've made furniture using classic Michoacán designs, in bohemian designs, in our own designs, and with every painted decoration you can imagine. You'll find anything from a still life of hybrid roses to a caricatured cat on our furniture and home decor. Our artists, wonderfully inventive talents, can take the simplest thing and bring it to a level of beauty that attracts the most discriminating client.

Another artist's workspace at UNEAMICH mfa/eronga.

"The work that comes from our talleres has spread all over the world. Right now, we're working on furnishing a hotel–not the first one, and we surely hope not the last! Disney commissioned pieces for a restaurant, we have other long-time restaurant clients who decked out their restaurant with our pieces and need frequent replacements, and we have years of background making custom pieces for private customers.

The man carving intricate hand-drawn orchids into this chair back said, "Solo soy carpintero." ('I'm just a carpenter.')

"Our stories range from the sublime to the truly ridiculous. We've gone through times of terrible famine, when we couldn't make our payroll–think of the horrors of the 1994 devaluation of the peso! But our artist workers stayed with us, even when we couldn't pay regularly. Really, it's the workers who have always made our business a success. You don't measure success just by looking at your bank balance. Loyalty to one another: that's a huge measure of success, in my mind.

For your home, mfa/eronga sells cinema seating made in the old-fashioned style, but of new materials–and in this case, painted with artists' stylized portraits. Other styles are available. Photo courtesy mfa/eronga.

"Right now, because economic times are really challenging, Steve is staying across the border in Tucson, running our retail operation. I'm here with our youngest daughter, running the talleres. Our staff here in Erongarícuaro currently numbers about 43, down from a high of 160 working artists. But we keep on going; our loyalty is to our cooperative artists, and their loyalty is to the cooperative and to us.

Nothing is wasted, everything is recycled. Out of this chaos of wood trimmings come works of art.

Flowers in a vase, hand-painted on an artist's workspace wall. Making art is more than a job; art is a way of life.

If you're planning to be in the Morelia/Pátzcuaro region, please contact Mexico Cooks! for a guided tour of Erongarícuaro, the mfa/eronga workshop, and more entrancingly beautiful villages in Michoacán.

Cactus in bloom on mfa/eronga chair backrests.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.