Mexico Cooks! originally published this article in June 2007, in a slightly different form.

Sra. Abundis, a Guadalajara friend, prepared this clear gelatina (gelatin). It's approximately 15" in diameter and stuffed with fresh red and green grapes, canned pineapple, and duraznos en almíbar (peaches canned in syrup).

Whether you're having a midday meal at a traditional Mexican restaurant anywhere in the República or celebrating at a private party at the home of Mexican friends, you can be almost 100% sure that a prominent item on the dessert menu will be gelatin. As you browse the produce at any town's tianguis (street market) or elbow your way through the crowds at a fiesta patronal (patron saint's celebration), you'll see vendors selling plastic cups and glasses of jewel-colored gelatin desserts. Gelatina is a shimmering sweet fact of life in Mexico, popular with young and old alike.

What is this Mexican obsession with a food that smacks of 1950s Middle America? Delight in gelatin desserts has been prevalent in Mexico for years; marketing experts here report that it's eaten daily in nearly 90% of Mexican homes. Mexicans consume more gelatin desserts than nearly any other country in the world—three times the quantity of gelatin consumed in the United States alone. In restaurants, the dessert tray will almost always include a variety of gelatin desserts. When Señora Fulana (Mrs. So-and-So) is invited to a party at the home of her best friend, it's very traditional for her to take along a gelatin dessert, all fancied-up and ready for the admiration of the rest of the attendees. At a birthday party, the dessert of preference is rarely cake and ice cream. It's almost always a plate of cake and a jiggling serving of gelatin, which requires no refrigeration to maintain its shape.

There are far more ways to prepare gelatin desserts in Mexico than your mother's Jell-O mixed with fruit cocktail or shredded celery and carrots. Some of the desserts are prepared with water, some with milk, and some are prepared as a layered combination of both. Some are major productions involving hours of labor intensive preparation time. And trust me when I tell you that housewives closely guard their recipes for gelatin desserts, not sharing among themselves unless the recipient of a recipe swears on her life that she will never take that dessert to a party where the other lady is also invited.

Sra. Abundis and her daughter Cristina prepared and painted this marvelous tiger gelatina for a child's birthday party.

Several months ago it was my task to prepare individual serving cups of gelatin for a two-year-old neighbor's birthday party—it seemed like I made hundreds. I thought it would be a complicated and difficult project, but it turned out to be quite a lot of fun. After asking another neighbor's advice, I learned that it's possible to buy powdered gelatin at any dulcería (candy store) or grocery store. The variety of available flavors is amazing: in addition to the ordinary strawberry, lime, and orange, I also found pistachio, almond, tamarindo, jerez (sherry), and peach.

While I could have kept my project simple, I decided instead to get fancy. No single-flavor cups of gelatin for this party! I read the directions printed on each bag and learned to prepare this flavor with water, that one with milk. I combined a layer of strawberry (prepared with water) with a layer of pistachio (prepared with milk). Recklessly, I disregarded the instructions to use water to prepare the peach flavor and used milk instead, combining an opaque peach-flavored, pale layer with a clear, bright orange-flavored layer.

Commercially made in Guadalajara for sale in Mexico's supermarkets, this three-layer single-serving gelatina includes a clear-gelatin fruit layer (complete with a prune and its pit), a milk-based layer, and a clear layer. The gelatina comes with its own tiny yellow plastic spoon. These 200 gram gelatins are prepared with preservatives and artificial coloring. Each one costs about 8 pesos, or 70 cents US.

It's so simple. Of course you can do this at home, even north of the border. Just buy two different flavors of your favorite brand of gelatin dessert powder, some four-ounce plastic glasses, and have at it. Prepare one flavor and fill each glass to the half-way point. Refrigerate and allow that flavor to set. Prepare the second flavor, using either milk or water, pour it on top of the already jelled flavor, and refrigerate until set. For me, this was fancy–but reader, read on!

The preparation of gelatin desserts has been raised to a fine art in Mexico. Special classes in gelatin preparation fascinate housewives and give rise to thriving cottage industry here. Recipes metamorphose from the relatively simple preparations like mine to the most elaborate of flavor and design combinations. A few years back, the craze for making individual clear gelatin desserts which contain flowers also made of gelatin has hit Mexico like a bombshell.

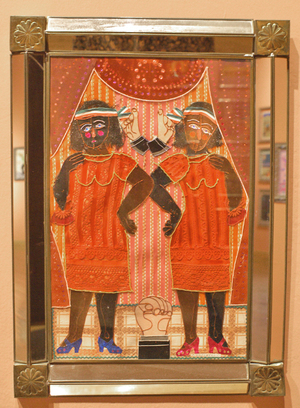

Flower gelatins like this one, made and copywrited by the Abundis family, are called gelatinas encapsuladas. The flowers are made by injecting colors of gelatin and flower designs with a syringe into clear or transparent gelatins. Neither Sra. Abundis nor Cristina took classes in making the flowers, although many handicrafts schools and individuals offer those courses.

This week I was fortunate to spend some time with Sra. Abundis and her daughter, Cristina, who operate a small home-based business in Guadalajara. The Abundis family invited me to come watch and take pictures as they prepared special gelatinas for a child's birthday party. Mother and daughter have worked together for the last two to three years, preparing made-to-order gelatins for birthdays, baptisms, girls' fifteenth birthday parties, baby showers, engagement parties, and weddings.

The gelatina personality of the day was Spiderman. Cristina explained that the gelatin for the Spiderman mold and many more are milk-based, while other gelatins are water-based. Milk gives the gelatina a more nutritious aspect than does plain water and also makes Spiderman's features show up better after they're painted.

In the Abundis kitchen, Spiderman is fresh out of the mold. A selection of milk ingredients is lined up behind him, along with a small plate full of individual-serving Spiderman heads.

Sra. Abundis showed me the basic ingredients for the dessert; once the basics are assembled, they're flavored with vanilla. Spiderman is prepared with powdered milk. Other gelatinas are made with sweetened condensed milk or with evaporated milk. The Abundis family uses pure cane sugar and unflavored gelatin for its desserts. No preservatives are added. These home-prepared gelatinas must be consumed within 48 hours of their preparation.

Many fancy gelatinas are painted once they're chilled and set. Spiderman is no exception. The paints are special vegetable food coloring gel, manufactured in Guadalajara.

Sra. Abundis watches closely as Cristina paints Spiderman's red base coat.

While Cristina painted, Sra. Abundis told me that when her relatives moved from Mexico City to Guadalajara in 1940, there was no powdered, flavored gelatina available in the city. Finally the relatives found a source–one stall at the Mercado Corona in Guadalajara's Centro Histórico sold it.

Cristina starts the initial work with black gel food coloring, outlining Spiderman's eyes. She holds a licenciatura (bachelor of arts) in graphic design from the University of Guadalajara.

"The gelatina has to be very cold in order to paint it," Cristina commented. "If it's not as cold and firm as possible, the paint will run." Spiderman stayed briefly in the freezer between coats of food coloring gel.

Spiderman's intricate thread work is complete.

I asked Sra. Abundis and Cristina which molds are most popular for parties. "Right now, Spiderman is the one all the kids want. Of course they also like Buzz Lightyear, Sponge Bob, all the Disney princesses, and Barbie. The old favorites like Winnie the Pooh, Mickey Mouse, and Tweetie Bird are always popular."

Josua Isai Abundis Linares, Cristina's now nearly nine year old nephew, participated eagerly in the time I spent with his family. He and I both anticipated our dessert: one of the individual Spiderman heads.

Cristina added, "For adult parties like weddings and baby showers, people want gelatinas encapsuladas, the ones with the flowers, to accompany their special cakes. And it's funny, the kids gobble down their gelatinas, but the adults want to save theirs. The flowers are so beautiful."

Cristina shows off the finished product: Spiderman in person! Sra. Abundis painted the blue base. The cost of this fantastic super hero is 130 pesos, approximately $11.50 USD.

"The people who ordered this Spiderman for their child's party will pick it up late this afternoon. The party is tomorrow." Cristina was happy that she finished the painting with no smears.

One traditional recipe is for Mousse de Rompope (eggnog-flavored gelatin dessert). This preparation is appropriate for dessert at any party for adults. It is so delicious that it bears repeating now.

Rompope (Eggnog) Mousse with Strawberry Sauce

Ten to twelve servings

Ingredients

Mousse

2 envelopes of unflavored gelatin

1/4 cup water

1 cup heavy cream

2 cups rompope (Mexican eggnog flavored liqueur)

1/4 teaspoon vanilla extract

4 egg whites

Strawberry Sauce

1 pound strawberries, stems removed

2 tablespoons sugar

1 tablespoon almond extract, anisette or Frangelica (hazelnut flavored liqueur)

Preparation

In a small bowl, sprinkle the gelatin onto the water and let stand until absorbed, about five minutes. Meanwhile, heat the cream slightly in a small saucepan. (Do not boil.) Remove from heat and stir in the gelatin, mixing well to dissolve. Strain into a bowl; add the rompope and vanilla and mix well. Set aside.

In a large bowl, beat the egg whites until they form stiff peaks. Fold in the eggnog mixture, and then pour into a lightly greased 1.5 quart ring-mold, bowl or specialty-shape pan. Refrigerate at least four hours, preferably overnight.

Place strawberries, sugar and flavoring in a bowl and let stand for two hours. Purée in a blender, strain and set aside.

Just before serving, remove the mousse from its mold and drizzle with strawberry sauce. Garnish with slightly sweetened whipped cream. If desired, the mousse can be molded with a graham cracker crust.

Provecho!

For dessert after your comida (midday main meal), for a snack or for a light supper, sweet wiggly gelatina satisfies every time. Cooling and slithery, a gelatina is just the ticket when you need a little something, but you don't want too much. They knew what they were talking about, way back then, when they said, "There's always room for…"

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.