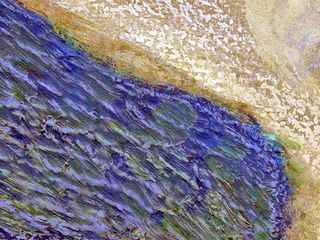

The agave atrovirens cactus. This enormous blue-gray plant, native to the ancient land which became Mexico, continues to provide us with pulque (POOL-keh), a naturally fermented alcoholic beverage. The maguey, with pencas (thick, succulent leaves) which can grow to a height of seven to eight feet, matures in ten to twelve years. At maturity, the plant can begin to produce liquor.

Pulque, native to Mexico, is suddenly all the rage in countries far from its origin. Folks who have never seen a maguey cactus 'on the hoof' argue the relative merits of natural versus flavored pulques, canned versus straight from the barrel, and so forth. Mayahuel, the goddess of the maguey, is laughing up her sleeve at this current rash of pulque aficionados: pulque has been well-loved in what is now Mexico for longer than humankind can remember.

Legend has it that a thousand years ago and more, Sr. Tlacuache (Mr. Opossum) scraped his sharp claws through the heart of the maguey and slurped down the world's first taste of pulque–and then another, and another, until he had a snoot full. His meandering drunken ramble allegedly traced the path of Mexico's rivers.

A drawing from the Codice Borbónico (1530s Spanish calendar and outline of life in the New World) shows Mayahuel, goddess of the maguey, with a mature cactus and a pot of fermented pulque. The first liquid that pours into the heart of the maguey is called aguamiel (literally, honey water); legend says that aguamiel is Mayahuel's blood.

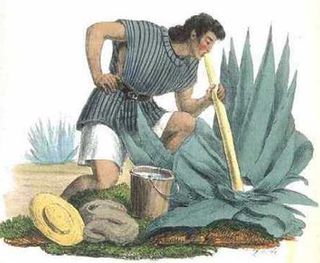

Aguamiel actually comes from the pencas (leaves) of the cactus. In order to start the flow of liquid into the heart of the plant, the yema (yolk) of the plant is removed from the heart and the heart's walls, connected to the leaves, are scraped until only a cavity remains. Within a few days, the aguamiel begins to flow into the cavity in the heart of the plant. The flow of aguamiel can last anywhere from three to six months. Today, the men who work the maguey to produce pulque are still called tlaquicheros. The word is derived from the same Nahuatl origin as the name for the original tlaquichero: Sr. Tlacuache, Mr. Opossum.

An early tlaquichero removes aguamiel from the heart of the maguey by sucking it out with a long gourd. Today, workers use a steel scoop to remove up to six liters of aguamiel per day from a single plant. Aguamiel is not an alcoholic beverage. Rather, it is a soft drink, sweet, transparent, and refreshing. Once it ferments, however, it becomes the alcoholic drink pulque, also known as octli.

The fermentation of pulque can start in the plant itself. Aguamiel, left in the plant's heart to 'ripen' for a few days, begins to ferment. For the commercial production which began in the 19th century, tlaquicheros remove aguamiel from the maguey and transfer it to huge steel tanks, where it ferments.

The heart of the maguey, full of aguamiel. The tool balanced in the liquid is the same type gourd that is pictured in the early drawing seen above. Between extractions of aguamiel, the leaves of the maguey are folded over the cavity where the liquid collects to prevent insects and plant debris from falling into the heart.

Mexican photographic postcard dating to the 1940s or 1950s. The women and children pose in front of huge maguey plants.

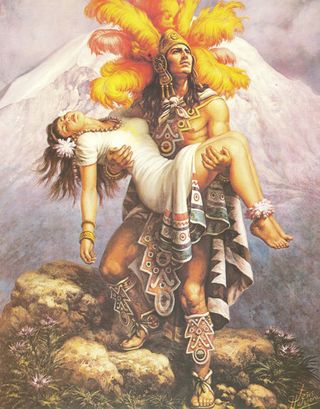

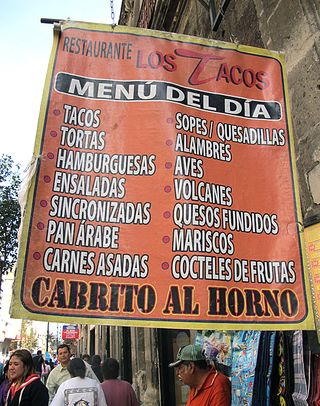

By the end of the 19th century, pulque was enormously popular among Mexico's very rich and very poor. Weary travelers in the early 20th century could find stands selling pulque–just for a pickmeup–alongside rural byways. Travelers riding Mexico's railroads bought pulque at booths along the tracks. Pulquerías (bars specializing in pulque) were in every town, however small or large. In Puebla and Mexico City, legendary pulquerías abounded.

Italian expatriate Tina Modotti, a member of the Diego Rivera/Frida Kahlo artists' circle, photographed Mexico City's pulquería La Palanca in 1926.

This common image hung in pulquerías all over Mexico. Clients could order the amount of pulque they wanted according to the drawings–and be reminded of what they had ordered when the pulque had laid them low. Image courtesy of La Voz de Michoacán.

In the foreground are the actual pitchers and glasses used in Mexico's pulquerías. Compare them with the vessels in the drawing. Image courtesy of Museo del Arte Popular (DF).

Pulque lovers spent long evenings in their favorite pulquerías in an alcoholic haze of music, dancing, laughter and delight. Far less expensive than other hard liquors, pulque carries with it the romance of ancient legend, the tradition of a nation, and the approbation of the gods.

Edward Weston, American photographer, immortalized Mexico City's pulquería El Charrito, also in 1926.

Natural pulque is a pale white, semi-viscous, liquid with a slick, thick feel in the mouth; many people are put off by that feel, as well as by its slightly sour taste. Even for those who dislike natural pulque, another kind of pulque–called curado (in this instance, flavored)–is delicious. Natural pulque, combined with blended fresh fruit, vegetables, or ground nuts, becomes a completely different drink. Bananas, guavas, strawberries, and the tuna (fruit of the nopal cactus) are particular favorites.

Feria de Pulque (Pulque Fair) in the State of Mexico. Each of the jars holds pulque curado, each flavored with a different fresh fruit, vegetable, or type of nut.

Mexico Cooks! first tasted pulque about 30 years ago, in Huixquilucan, in the State of Mexico. Huixquilucan, known to its inhabitants as Huixqui (pronounced whiskey), used to be a small town, and Mexican friends took me to its small-town fair where home-made pulque was for sale in what seemed like every booth offering food and drink. "Try it, you'll like it a lot!" my friends giggled. "Just a little taste! C'mon!" I was nervous: I'd heard about pulque and its slippery slimy-ness and its inebriating qualities. Finally we stood in front of a booth offering pulque curado con fresas: pulque flavored with fresh strawberries. "Okay, okay, I can try this." And I liked it! The first small cupful was a delicious, refreshing, slightly bubbly surprise. The second small cupful went down even more easily than the first. And then–well, let it be said that I had to sit down on the sidewalk for a bit. I truly understood about pulque.

Try it, you'll like it a lot…c'mon, just a little taste!

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.