It occurred to me earlier this week to re-publish this Mexico Cooks! article, originally published in 2007, when I read an article in the New York Times about a beautifully restored house in Concepción de Buenos Aires. I loved being in the town, and I remembered my day there with much fondness as I read the newspaper article. I only wish I had known all those years ago about the lovely home.

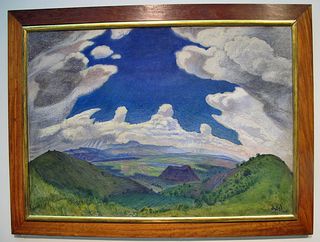

The road to Concepción de Buenos Aires.

The drive deep into the mountains was long, more than two hours from my home in Guadalajara. Many kilometers of the twisting road were rough, pocked with deep potholes. I got stuck behind a slow-moving slat-side truck full to the brim with plastic bags of raw chicken, huge crates of vegetables and fruits, bags of bread and other foods. I was in a hurry to reach Concepción de Buenos Aires, a tiny town well off the beaten tourist path, where I was to meet Sr. Cura Manuel Cárdenas Contreras, the pastor of la Parroquia de la Inmaculada Concepción—the parish of the Immaculate Conception. I'd heard a little about him and his healing work from an acquaintance, but I really couldn't imagine what lay in store for me.

When I arrived, I discovered that it was tianguis (street market) day in Concepción de Buenos Aires. The streets around the town square were closed, blocked by vendors' booths. Rock music blared and the dusty cobblestones were crowded with men in jeans and cowboy hats, women in red-checkered aprons buying vegetables for the day's comida (dinner), and little children tugging at their older siblings' hands as they pleaded for a candy or toy. I squeezed into a parking space and navigated through booths of bolis (a frozen treat), flower arrangements, and DVDs to get to the parish steps.

I made my way through the church to its inner courtyard, where there was a great deal of bustle. A big truck—the very loaded-down truck I had followed along the road to town—was being emptied. One of the women helping with the truck explained to me that all of its contents had been donated for the poor of the town. The food was being divided into bags for individual families. "We do this every week," she beamed. She led me to the entrance to the parish office. "He's in there, just go on in," she encouraged me.

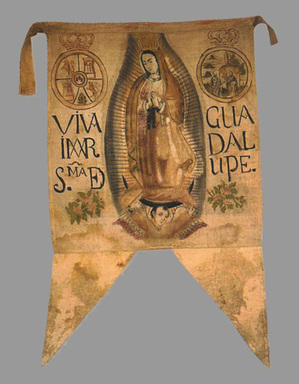

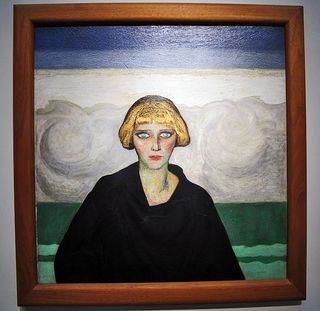

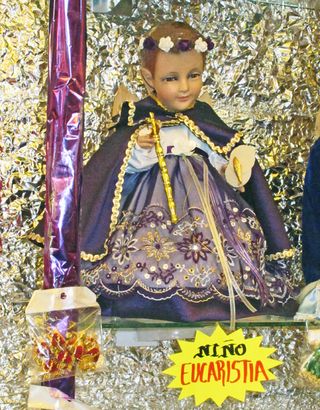

La Inmaculada

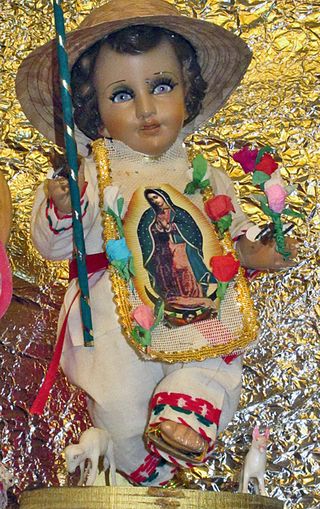

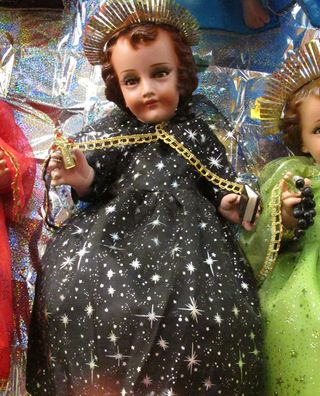

Religious pamphlets, candles, and pictures crowded sales shelves in the dim anteroom. What I assumed to be the secretary's desk was unoccupied. I waited a moment for a prior visitor to come out of the priest's office. When the visitor left, a gravelly voice welcomed me. "Come in, come in."

Padre Manuel rose to greet me and we chatted for a bit. A steady stream of townspeople arrived to schedule Mass intentions. "I'll close the office at 12:30," he said, "and we'll go over to the house to talk further. We can have some privacy there."

Just then a tiny elderly woman wrapped up in a shawl came into the office. She was looking for the church secretary, who was indeed taking the day off. Padre Manuel said, "What do you need?"

She said, "I'm looking for a hand."

Father Manuel held up one of his, fingers spread apart. "Here's one."

"Ay, padre, not yours, no no no. It's that I fell and broke my hand, and I promised the Virgin if it got well I'd hang up a hand to say thank you." She wanted to purchase a small milagro, a metal token that she'd hang near an image of the Virgin as a way to say thank you for her healing.

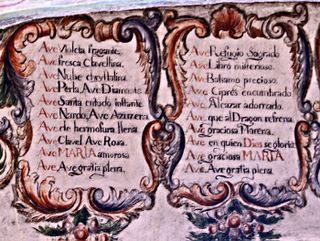

Detail above the altar of La Inmaculada.

He asked to see her hand, which from where I was sitting looked bruised and still a bit swollen. He started rubbing her hand a little and she winced. He said, "You have sugar, don't you?"

"Sí, padre." She nodded her admission of diabetes.

"And I can tell that your hand still hurts. Who were you fighting with?"

"Ay, padre, I fell down!" She giggled. "I guess I was fighting with the ground. The doctor just took the cast off and yes, it still hurts."

He prodded at her hand with his big fingers and then yanked her little finger. Then he prodded around her thumb and yanked a bit. "Move your hand." She tentatively moved her fingers. "No, really move it, bend it, make a fist, wiggle your fingers."

She did, and a slow beautiful grin spread across her face. "It doesn't hurt!" He grinned and nodded.

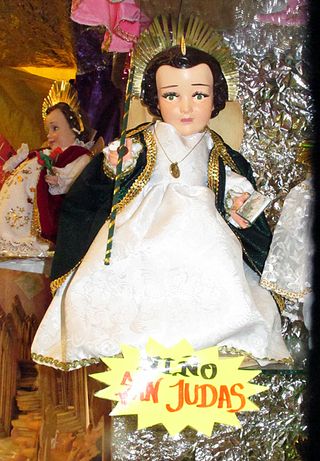

Milagros mexicanos, including human body parts, animals, and other symbols.

Then he said, "How's your hearing?"

"Ay, padre, since my husband died three months ago I can't hear, my ears are stopped up." He put an index finger into each of her ears and snapped them out again in an abrupt motion. Then he tapped one of his index fingers, hard, on the crown of her head. And again. Then he whispered, "What is your name?" No reaction. A little louder. No reaction. And again, this time very loud.

"Consuelo Álvarez Martínez, padre."

He repeated his ministrations, and from behind her, whispered very softly in her ear again. "What is your name?" She answered instantly.

Then he said, "You have trouble with your blood pressure, right?"

"Sí, padre." He put his hand high on the bony part of her chest and pressed hard. Then he asked her if she got dizzy when she bent over.

"No, padre, but after I bend over and then stand up, I get dizzy."

He said, "Try it."

She did. "A little, padre."

He pressed on the bony part of her chest. "Again."

"Ay padre, still a little."

"Now try." And she said she was fine, no dizziness.

It was all very matter of fact. There were three other people in the room, including me. She went happily on her way, saying she'd be back the next day to pay her debt to the Virgin.

In just a few minutes, Padre Manuel finished writing up the Mass intentions and ushered me through the church, down the sacristy steps, and into the spacious office where he receives people who are looking for his help. Settled at his desk, he began talking about his life.

"I was born in 1931 in Valle Florido, a rancho that's part of the municipality of Concepción de Buenos Aires, to Manuel Cárdenas García and Petra Contreras Cárdenas. I never knew my father. He was killed by eight men just six months after he married my mother. She never remarried, so I was an only child. When I was seven years old, I started primary school out in the country.

"By the time I was thirteen, I had started thinking about what I wanted to be when I grew up. In those days, there were only a few options. The diocesan seminarians from Guadalajara came out to the rancho on vacation in August that year, and I began to be interested in knowing more about God. I liked the catechism and I decided to go ahead and enter the junior seminary.

"For the first two years, I studied in Tlaquepaque to finish school. Then I entered Señor San José Diocesan Seminary in Guadalajara. After I studied three years of theology in the diocesan seminary in Mérida, I finished my theology studies in Guadalajara and then was sent to the state of Tabasco. I was ordained a priest in Tabasco on July 9, 1961, by Archbishop Fernando Ruíz Solórzano."

Padre Manuel paused and tapped a finger on his desk. "How long were you in Tabasco, Padre?" I asked.

"Sixteen years, all told. Then at the request of the bishop of Ciudad Guzmán, I came back to the archdiocese of Jalisco."

I was puzzled. "How is the archdiocese of Jalisco divided, Padre? I didn't know there were other diocesan divisions."

He smiled. "Yes, we have the archdiocese, with its base in Guadalajara. Then we have three other diocesan seats within the archdiocese: Ciudad Guzmán, San Juan de los Lagos, and Autlán." He ticked the names off on his fingers. "So I was called to the diocese of Ciudad Guzmán and came back to Concepción de Buenos Aires on April 30, 1973. Then in May, I was called to Tuxpan to help with the fiestas of Nuestro Señor del Perdón. On June 13, 1973, I was named pastor at the parish of Teocuitatlán de Corona, in Jalisco.

"I was there for nearly ten years, and then I was asked to be pastor at another parish in Jalisco.

"Finally, in 1994, I was named pastor here at La Inmaculada, in my home town of Concepción de Buenos Aires. And I've been here ever since, eleven years now." He shook his head incredulously at the rapid passage of time.

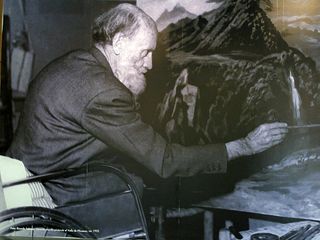

El Señor Cura Manuel Cárdenas Contreras

"Padre Manuel, many people have told me about your remarkable ability to bring about miraculous cures. Tell me something about how that started."

He leaned forward and looked intensely at me. "I don't cure. God cures. I'm only the means. As a human being, I don't really understand what happens.

"More than twenty years ago, I suffered a lot from terrible back pain that affected my right leg. For eleven months, the pain was intense, day and night. I went to many different doctors, different specialists, as I looked for a cure, but the pain wouldn't leave me and the doctors weren't able to cure me. I was desperate.

"In one of God's mysteries that we as human beings can't understand, I was sent to a doctor, a specialist, in Guadalajara. He was a trained medical specialist, but he also used alternative healing methods. He utilized an alternative energy, he did some things that I can't explain even now. In twenty minutes the pain was gone and I could stand up straight. I went back twice more, and I was cured." Padre Manuel held out his hand and drew in his breath.

"The doctor told me that I also had the gift of healing. I told him no, no I didn't. He said yes, yes I did, and that he would teach me how to use the gift. I refused, over and over again.

"Then one day the doctor said to me, 'So, you wanted to be healed, but you don't want to be an instrument of healing? You wanted to receive, but you don't want to give back?' That stopped me in my tracks. How could I continue to refuse?"

I felt a chill run through my body as I listened to Padre Manuel tell his story. "Please go on," I encouraged him.

"The doctor asked me to come back four times a week, four hours a day, for four months. He said in that length of time he could teach me to use the power for healing that he felt in me. He taught me about the positive energy that comes from women, the negative energy that comes from men, and how they complement one another, the yin and the yang. He taught me about chakras and auras, he showed me how to use ordinary scissors to effect healing.

"I've talked to thousands of people since then, from all social classes. People with health problems come here from everywhere, eager to be healed. Now I'm only able to see people on Fridays and Saturdays. Working in this way is extremely draining, very tiring.

"Recently a family brought one of their daughters to me, all the way from Texas. When she came, she was walking with crutches, with great difficulty. The girl had just had an operation that cost $40,000 USD, an operation that the doctors told the family would allow her to walk again. The operation was a failure." Padre Manuel pointed to my left. "Look, those are her crutches. When she left here, she could walk as well as you can."

I felt the sharp sting of tears in my eyes. "A friend of mine came to you a few years ago, with terrible back pain. Maybe you remember him—Eufemio García?" Padre Manuel nodded.

I reminisced about his story. "Eufemio had rescued an enormous old crippled dog that had to be bathed frequently to keep her from smelling bad. He used to strip down and hose her off in his patio so he wouldn't make such a mess in his house. One evening he bathed her, let her in the house onto the tile floors, and she slipped and couldn't get up. Eufemio tried to lift her and he slipped, doing the splits on the tiles. Not only had he pulled his muscles, but he developed a bad back injury that prevented him from taking anything but baby steps. He couldn't walk up a flight of stairs and he couldn't step up onto the high curbs we have here. Some other friends brought Eufemio up to Concepción de Buenos Aires to see you."

Padre Manuel took up the thread of the story. "You know, I cure using scissors. Of course the scissors never touch the person, but they draw energy and cut pain and—well, we don't know exactly how it works, but it does. If I remember your friend, he's a big man, right?"

"Yes, Padre, he's well over six feet tall. Not as tall as you are, but tall."

Padre Manuel nodded. "I would have had him stand in front of me while I passed the scissors over his head, his neck, and down his back. It doesn't sound so impressive or important, but what did he tell you happened to him?"

"He told me that he could have sworn you pressed the scissors against his body as you worked with him. He said he felt their pressure, but one of his friends who was here that day insists that the scissors never touched him. He felt them move over his body in just the way that you described."

The priest nodded again. "She's right, the scissors never touched him. What else did he tell you?"

I thought for a moment. "He said that the pain lessened immediately. He said you told him to bend and touch his toes. He could do it, and there was no pain. Then you asked him to do some knee bends, and again there was no problem. He said he could take normal steps right away, and in about ten minutes he was completely back to normal. He told me he took some teas that you'd prescribed to supplement the healing. He said his pain never came back and he's had no problem with his back since then."

Once again Padre Manuel nodded. "That's excellent, I'm so glad to hear it. Tell your friend to treasure his health.

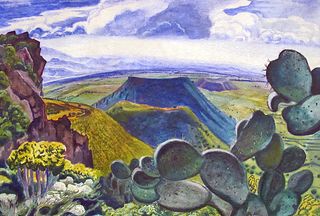

Blue agave–tequila–fields near Concepción de Buenos Aires

"You know, a Japanese woman, a chemist in Tapachula, brought her daughter to me because she couldn't raise her arms or use them. Now that she has been here, she can. In Spanish, we have a dicho (saying): Querer sanar es media salud (to want to be healed is half of health). I can't explain the mysteries of God in curing people of their problems, but I know it is God who cures. What I do is work with God's energy and the energy of the person who has the illness. That woman you saw in my office earlier today? With God's help, her problems will be healed.

"Just tell people that it is God who heals, it's not me." Padre Manuel clasped my hands and walked me to the door of the church. "Remember, I'm the instrument." He bent down and hugged me. "Vaya con Dios."

Here's a link to the beautiful New York Times article. Architect's Home in Concepción de Buenos Aires Enjoy!

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.