Those of us from the United States and Canada can recognize many of the historical landmarks and buildings in our native countries. We know by sight the Parliament buildings in Ottawa and the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. Even when we think of important historical tributes in foreign countries the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, the Parthenon in Athens, the ancient pyramids of Egypt pop instantly into our minds. These are cultural icons that cross international barriers.

Here in Mexico, most of the historical monuments and landmarks are less well known to foreign travelers. Even Mexican history is fuzzy and confusing for most of us. When we’re first living the expatriate life here, it seems that every other holiday on the calendar is an Independence Day of some sort. The reasons for frequent patriotic parades escape us and the flowery language on commemorative plaques can be baffling, even if we’re fluent in reading Spanish.

Here’s a nutshell tour complete with photos of some of the more prominent sites and monuments in Guadalajara.

When I first visited Guadalajara in the early 1980s, I could not imagine what the blue logo on the trunks of taxicabs could be. It looked like a line drawing of a Batman-ish cap with pointy ears. Finally one day it dawned on me that the logo was really the dome and spires of the Metropolitan Cathedral. Shaped like inverted ice cream cones and tiled in pale yellow, the design of the spires, legend has it, came from a mid-19th Century bishop’s dinner platter. Although the cornerstone for the Cathedral was laid in 1561, these beautiful spires were built to replace the originals, one of which fell to the ground in a strong earthquake in 1818. The spires contain sixteen bells, the oldest of which dates to 1661 and the newest from 1877.

Catedral Metropolitana de Guadalajara

The Cathedral has eleven altars and 30 Doric columns. There is a crypt below the main altar in which the remains of several bishops and cardinals are buried. In the sacristy there is a painting of the Immaculate Conception by Spanish master Murillo. On the facade of the Cathedral is an enormous plaque which reads in Spanish, ‘If the Lord does not build the house, the laborers work in vain.’

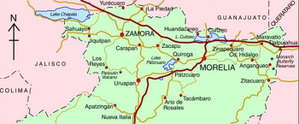

The Cathedral is located on the southeast corner of Avenida 16 de Septiembre and Calle Hidalgo in the Centro Histórico.

La Rotonda de Hombres Ilustres

The Rotonda de Hombres Ilustres (Circle of Illustrious Men) commemorates nearly 100 prominent and influential people who were born in the state of Jalisco. The Rotonda was built in 1952. It is composed of 17 striated columns without bases or capitals; these form a circular enclosure. The cremated remains buried in the enclosure include those of scientists, writers, artists, and educators, each of whom made Guadalajara a better place to live. In the year 2000, the remains of educator Irene Robledo, the first woman given this honor, were transferred to the Rotonda. Nineteen of the honored dead are represented by larger than life size bronze statues which surround the lovely green park of the Rotonda. On any Sunday—the day for family outings in Mexico—you will see Mexican parents proudly showing their children the details of the statues and their identifying plaques.

The Rotonda de Hombres Ilustres is located on the northeast corner of Avenida 16 de Septiembre and Calle Hidalgo in the Centro Histórico.

Teatro Degollado

The Teatro Degollado is not technically a monument, but it is certainly one of the more monumental structures in Guadalajara and is a major draw for tourists. The graceful Neoclassical architecture of the building and the Grecian frieze depicting Apollo and the Nine Muses along the top of the theater’s front combine in a classic piece of architecture. Along the theater’s back wall, a historical bronze frieze depicts the founders of Guadalajara. Each colorful Sunday morning presentation of the University of Guadalajara’s Ballet Folclórico attract hordes of tourists visiting the city from everywhere in the world.

Construction of the theater began in 1855 and the doors opened in 1866. It is named for a former governor of the state of Jalisco, Santos Degollado, whose remains are interred in the Rotonda de Hombres Ilustres. The theater’s opening production was Donizetti’s opera Lucia de Lammermoor, starring the "Mexican Nightingale", Angela Peralta. The theater, which seats more than 1000, has recently undergone major interior restoration to retain its original glory.

Teatro Degollado is located on Calle Belén between Calles Hidalgo and Morelos.

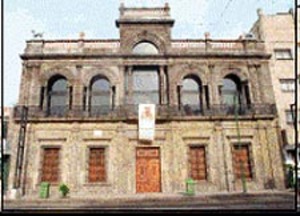

La Casa de los Perros

Just past the Cathedral on Avenida Alcalde you will see the Casa de los Perros, a huge house decorated with cantera (carved rock) and stained glass windows. Two enormous stone sculptures of dogs stand guard on the roof. The first printer’s shop in the city was located on this spot. Before the existing house was built, a print shop here published The American Alarm, which is considered to be the first independent newspaper in the Americas. Aside from its other architectural details, on either side of the top of the house you will see the much larger than life size sculptures of pointer dogs. These were brought to Guadalajara in the 19th Century from the J. L. Mott Ironworks in New York.

The house was opened as the museum of Guadalajara newspapers in 1994. The museum is open to the public Tuesday through Saturday from 10 AM to 6 PM and Sundays 10 AM to 3 PM.

The museum is located at Alcalde #225 in the Historic Center.

Plaza de Armas

The lovely and picturesque Plaza de Armas is surrounded by a series of important buildings including the Palace of Government and the Templo Metropolitano del Sagrario, built between 1808 and 1843. Central to the Plaza is the Art Nouveau wrought iron froth of the kiosco (bandstand), which was imported in 1909 by the French residents of Guadalajara as a gift from France. The bandstand roof is supported by eight caryatids (female figures nude from the waist up) which represent different musical instruments. When they were first installed, the nudes created a terrible scandal among proper turn-of-the-century tapatíos (residents of Guadalajara). The roof itself is formed of fine woods, which give special acoustic resonance to the bandstand. Tuesday, Thursday, and Sunday afternoons there are special public concerts in the kiosco, performed by the state or municipal bands.

The Plaza de Armas is located at the corner of 16 de Septiembre and Calle Morelos.

El Monumento a los Niños Héroes

The Monumento a los Niños Héroes (Monument to the Boy Heroes) commemorates the 1847 battle between the United States and Mexico at Chapultepec Castle in Mexico City. Chapultepec Castle was a military school and home; it was unable to withstand the battle waged by the U.S. forces.

During the course of the fighting, in which Mexico was defeated, one general and six young cadets lost their lives in defense of their country. Legend has it that when just one cadet remained, he wrapped himself with the Mexican flag and leaped from the tower to protect the flag from capture.

At the top of the monument is a feminine sculpture which represents Mexico. She wears a long tunic and holds a garland between her hands. At her feet is the national symbol of Mexico: the eagle, standing on a cactus and devouring a serpent.

At the bottom of the monument are statues of the child heroes who gave their lives for Mexico. The inscription in brass letters reads, "They Died for their Country." Each of the boys’ names is inscribed in gold.

The monument is located in the glorieta where Avenida Niños Héroes and Avenida Chapultepec intersect.

Beatriz Hernández

At one side of the Plaza de los Fundadores (Founders’ Plaza) behind the Teatro Degollado, the statue of Beatriz Hernández commemorates a woman who lives in the hearts of all Tapatíos. Most know her as the foundress of Guadalajara. Legend has it that she was a woman of strong and decisive character. One day, when the Spanish were indecisive about where exactly the new city should be founded, Beatriz Hernández asked to speak and counseled them that it should be in the Valle de Atemajac—just east of the area that today we call the historic center of Guadalajara. The statue in her memory is more than six feet high, a size as heroic as her personality.

El Monumento a la Independencia

Just south of the Historic Center on Calzada Independencia is one of the most beautiful public sculptures of Guadalajara. The Monument to Independence was built in 1910 as a commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the proclamation of Mexico’s independence and abolition of slavery. The monument consists of an octagonal base made of pink cantera (carved stone) and a cantera column with a study of Hidalgo, the father of independence, carved in white marble. Hidalgo is addressing his oppressed children who are beginning to rise up in the fight for liberty. The column features other white marble statues. One represents history (a woman with a book); another represents the national epic of Mexico (a woman with a long trumpet). At the top of the column is the angel of independence.

The Monument to Independence is located on Calzada Independencia at the point where it crosses Calle Corona.

I’ve saved three of my favorite Guadalajara monuments for the last. Each of them is near my house and I get to see all three nearly every day.

La Estampida

La Estampida (The Stampede) was designed and created by sculptor Jorge de la Peña. The horses are bronze and represent a group of horses in full gallop. Every detail of each horse is filled with dynamic action, power, and intense emotion.

La Estampida is located on Avenida López Mateos Sur at the glorieta (traffic circle or roundabout) called the Jícamas.

Glorieta and Fuente Minerva

The goddess Minerva, representing justice, wisdom, and strength, is one of the most famous symbols of Guadalajara. The fountain is in the center of a huge lawn-covered glorieta. The enormous bronze statue has at its feet the motto in Spanish, "Justice, Wisdom, and Strength, Custodian of this Loyal City". At the back is written in Spanish, "To the Glory of Guadalajara".

The names of eighteen illustrious Guadalajarans are engraved on the pedestal. The Minerva is the largest fountain in Guadalajara. Water erupts from the pedestal in a mist which offers an incredible scene to passersby and which can occasionally spray water onto motorists waiting to cross the glorieta. The statue was conceived by Pedro Medina and sculpted in Aguascalientes to be brought to Guadalajara and installed. The entire project was conceived by Agustín Yáñez, governor of the state of Jalisco from 1953 to 1959, to pay tribute to Guadalajara.

Arcos de Minerva

Built in 1942, the Minerva Arches commemorate the 400th anniversary of the founding of Guadalajara. They welcomed travelers at that time, when the location was the point of convergence of the important highways from Mexico City, Tepic, and Barra de Navidad.

The Arches are similar in design to the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. The motto on one side reads, "Hospitable Guadalajara" and on the other side, "A Wonderful Stay is the Guarantee of Your Return". The Guadalajara coat of arms, granted by King Carlos V of Spain, is featured on either side. The city Office of Tourism has been located in the arches since 1959. In the offices are permanent exhibits of Guadalajara memorabilia. Upstairs there is a vantage point where tourists can enjoy incredible views of the city. The monument is as well-recognized as a symbol of the city as the steeples of the Cathedral.