The simple whitewashed facade of Tupátaro's templo (church) of Santiago Apóstol (St. James the Apostle) belies the intense beauty inside. Note the pale-purple orchids blooming in the tree at the left.

The evangelization of Michoacán's Purhépecha tablelands, where many of the state's largest group of indigenous people live, was realized during the 16th and 17th centuries. Religious and secular orders who came to New Spain during the earliest part of the Spanish Conquest worked ceaselessly to convert the native peoples to Christianity. In the 16th Century, Franciscan and Augustinian priests worked together with the first bishop of Michoacán, Don Vasco de Quiroga, creating 'hospital-towns' all along a route through the mountains and valleys of Michoacán. Today, that route is still known as 'La Ruta de Don Vasco'

Bishop Vasco de Quiroga, an intellectual student of Thomas Moore's Utopia, saw in the area that is now the state of Michoacán an ideal place to put Moore's social theories to work. In Michoacán, Quiroga found a thriving crafts-driven economy, a well-developed and organized community, and the opportunity to lead the indigenous to higher and higher goals of barter and commerce. Although Vasco de Quiroga had already founded a similar 'hospital' in Mexico City, he invested his entire life in perfecting the idea throughout Michoacán's Meseta Purhépecha.

The retablo (altarpiece) in Santiago Apóstol is made of carved wood covered with 23.5 karat gold leaf. The six paintings in the retablo, painted by a single artist in the 17th Century, are oil on canvas.

Michoacán's pueblos hospitalarios ('hospital-towns') were evangelized in a manner unlike that in other regions of New Spain. The term 'hospital-towns' refers to the founding of towns specifically for the purpose of offering hospitality to the stranger and religious education as much as physical care for the sick. Each of the several pueblos hospitalarios was built along similar lines: they included a convent, a church dedicated to a particular patron saint, a smaller chapel dedicated to the Immaculate Conception, and a huatápera (meeting place), which was the actual hospital and travelers' hostel. The huatápera was the heart of the complex and the church was its soul.

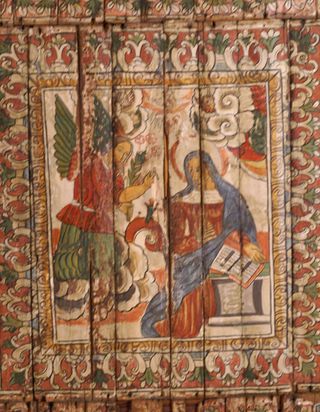

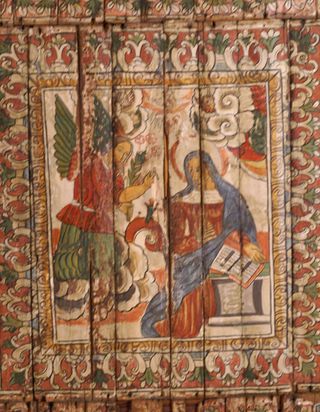

Religious architecture in the Purhépecha towns was characterized by the use of adobe brick and mortar walls and carved volcanic stone entryways. The roofs were originally made of tejamanil (thin pine strips) which were later covered with clay tiles. The jewel of the interior of the simple churches was the high ceilings. Either curved or trapezoidal, the entire wooden ceiling was profusely hand-painted by indigenous artists with images of the litanies of Mary and/or Jesus, with angels, archangels, and apostols. They are filled with symbols of medieval European Christianity adapted to the perspective of the native Purhépechas. Serving as decoration, devotion, and education in the faith, these churches and their ceilings, along with their finely detailed carved retablos (altarpieces), are some of the greatest artistic treasures of the region. Today, they are still an important part of the Route of Don Vasco.

El Señor del Pino (The Lord of the Pine), 18th Century crucifix venerated on the altar in Tupátaro.

For years, Mexico Cooks! has been fascinated with the Templo de Santiago Apóstol (Church of St. James the Apostle) in Tupátaro, Michoacán. The tiny church was founded by Spanish Augustinian missionary priests who arrived either with or soon after Don Vasco de Quiroga. Under the careful conservatorship of Mexico's INAH (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia), Santiago Apóstol is one of the small 16th Century churches in Michoacán that has been restored to its original glory. Frequently called the Sistine Chapel of the Americas, Santiago Apóstol of Tupátaro is one of the most important early churches of Mexico. INAH recently honored Mexico Cooks! with permission to photograph and write about this national treasure.

The highly revered statue of Santiago Apóstol (St. James the Apostle) stands at the left side of the church altar. Built on a platform made to be carried on townspeople's shoulders, the statue processes solemnly through Tupátaro every year on the saint's feast day.

The 500-year-old wood-plank floors, built over crypts, creaked as we entered the church and walked toward the altar.

Rays of sun semi-illuminate the six oil paintings of the retablo (altarpiece): the crowning with thorns, the flagellation, the way to Gethsemane, the prayer in the garden, the adoracion of the Magi, and, high above the rest, Saint James the Apostle on his horse. The angels on either side of Santiago Apóstol have mestizo (mixed race) faces; all six paintings were created by the same hand. The sense of antiquity and reverence are palpable in this early New World church.

Detail of alterpiece sections Santiago Apóstol (St. James the Apostle) and La Adoración (Adoration of the Magi).

The classic baroque carved wood columns of the retablo, covered with 23.5 carat gold leaf, are adorned with bunches of grapes, mazorcas (ears of corn), granadas (pomegranates), and the whole avocados which represent this region of Mexico. In addition, sculptures of four pelicans decorate the altar. The pelican, with its young pecking at its breast until blood flows from its flesh, is an early Christian symbol of Christ who nurtures his church with his blood.

Detail of the life-size pasta de caña crucifix, Templo Santiago Apóstol, Tupátaro. Pasta de caña, unique to the central highlands of Mexico, is made from corn stalk pulp mixed with paste from orchid bulbs. Shaped around a wooden or bamboo armature, the paste is allowed to harden. It's then carved, covered with gesso, and polychromed.

On the right of the altar stand carvings of the four evangelists: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. On the left are four Doctors of the Church: St. Gregory, St. Augustine, St. Jerome, and St. Ambrose.

The wooden bóveda (arched) ceiling, entirely hand-painted by indigenous serfs in the 18th Century, is the most spectacular feature of the church. The paintings include the Passion of Christ, twelve mysteries (stories to meditate) of the lives of the Virgin Mary and Jesus, 33 archangels holding Christian symbols (one archangel for each year Christ lived on Earth), and other religious and secular symbols.

This archangel carries the three nails used to hang Christ on the cross.

Each of the archangels wears distinct clothing, has a unique face, and different wings. Each stands on clouds. In the photographs, you can see that the lower sections of each panel are flat against the wall; the next two or three panels form the beginning of the boveda, and the higher panels curve against the ceiling. Each individual archangel panel measures three to four meters high; together they span both sides of the length of the church, from entrance to altar.

This archangel carries a Christian flag.

This archangel carries a sponge on a pole and a vessel filled with vinegar. When Christ said, "I thirst,", as he hung on the cross, he was given vinegar to drink.

La Anunciación (The Annunciation), one of the mysteries of the life of the Virgin Mary. The angel is telling her that she will be the mother of God.

La Ultima Cena (The Last Supper), a mystery of the life of Christ. The food on the table is food found in this region of Mexico.

La Resurrección (the Resurrection).

The panels showing the mysteries of the life of Christ begin at the front of the church and move toward the altar; the panels showing the mysteries of the life of the Virgin Mary begin at the altar and move toward the front of the church. Watermelons painted on the beams between the panels represent the blood of Christ.

This panel is positioned directly over the altar. In the center is a dove, the symbol of the Holy Spirit.

The ceiling panels and other paintings were painted directly on wood, using tempera paint made with egg yolks. Vegetable and earthen dyes color the 18th Century paints, which have held up very well for nearly three hundred years.

The front panel of the altar, unique in the world, is made of pasta de caña, linen, cotton, and silver leaf. The dedication inside the oval reads, "Se hizo este frontal par al el Santísimo Cristo del Pueblo de Tupátaro a espensas de sus devotos y dando sus limosnas siendo Eusebio Avila año 1765." ("This altar front was made for the Most Holy Christ of the people of Tupátaro at the cost of his devoted followers and giving alms, being Eusebio Avila year 1765.") The panel was recently restored by Pedro Dávalos Cotonieto, a local sculptor who specializes in pasta de caña.

The tiny church has an exquisitely beautiful museum. Juan Cabrera Santana, the church caretaker and our exceptionally knowledgeable guide, showed us its treasures.

Sixteenth century saint, Museo Santiago Apóstol.

La Santísima (The Holy Virgin Mary), fresco, Museo Santiago Apóstol.

Tupátaro, Michoacán town plaza.

Mexico Cooks! is grateful to INAH (the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia) and to Juan Cabrera Santana for their kind permission and guidance in bringing the Tupátaro Templo de Santiago Apóstol to our readers.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.