Actúa por la Paz: Take Action for Peace, on the back of a T-shirt, Morelia, September 15, 2009.

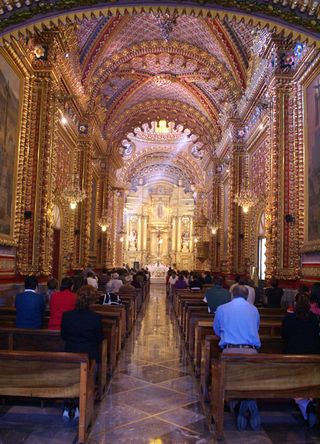

On the night of September 15, 2008–just a bit over a year ago–all of Mexico celebrated its annual re-enactment of the Grito de Dolores (1810 call for independence from Spain). Many of Morelia's citizens, filled with the joy of Fiestas Patrias (Independence Day) festivities, gathered in the two downtown plazas facing the balconies of the Palacio del Gobierno (state capitol building) to await the appearance of Michoacán's governor. Traditionally, the governor waves the Mexican flag, rings a bell, and calls out a string of VIVAs: Viva México! Viva Hidalgo! Viva Morelos! Viva la Corregidora! Viva los Niños Héroes! Viva México!

In Morelia, those historic VIVAs are always followed by glorious patriotic fireworks in front of the Cathedral. At the 2008 celebration, the governor's actions were aborted by a loud explosion: instead of fireworks, the sound was from two live grenades thrown into crowded Plaza Melchor Ocampo. The balance: hundreds injured, eight killed, and scores of lives changed forever. Recovery of confidence has been slow in Morelia; we who live in Morelia lost our innocence that night.

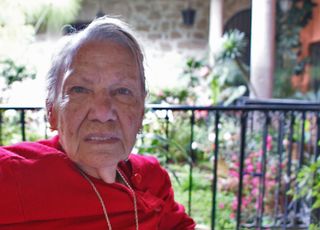

Rigoberta Menchú Tum from Guatemala, 1992 winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, moved hearts and minds with her Ceremonia por la Paz (Peace Ceremony) speech on September 15, 2009, in Morelia.

The event didn't look much like a ceremony for peace, but rather resembled a locked-down security risk. Morelia's Centro Histórico, an area that encompasses most of our colonial-era buildings, was cordoned off by Federal, State, and local police. No private vehicles, taxis, or buses were allowed to circulate within a several-square-block area of the Cathedral. Pedestrians who wanted to enter the area passed first through metal detector security arches. Federal police checked all handbags, camera bags, and backpacks for suspicious objects.

Just across the street from Plaza Melchor Ocampo, sharpshooters and special security forces lined the roof of Hotel Los Juaninos. In order to enter the plaza, we had to pass under yet another security arch. Friends who work for the government called out to us to sit with them for the event.

Fausto Vallejo Figueroa, mayor of Morelia, greets supporters at the Ceremonia por la Paz.

Once settled, we looked around at the crowd. Government officials of all ranks, university officials, relatives of the 2008 victims, and a few selected schools were present, but no ordinary Morelia citizens were in the chairs. The press was amply represented. It became apparent that this Ceremonia por la Paz was more a photo opportunity and sound bite for government promotion than it was an event for the common person.

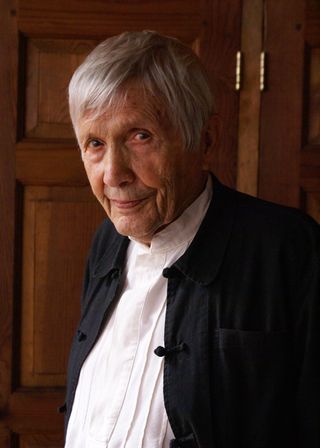

Dra. Silvia Figueroa Zamudio, distinguished rector of the Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo. Dra. Figueroa, whose term began in 2007 and will end in 2011, is the first woman rector since the university was founded in 1540.

Leonel Godoy Rangel, governor of Michoacán, chats with Rigoberta Menchú prior to her Morelia speech.

In spite of the militaristic aspects of the event, Sra. Menchú exhorted Morelia, "Don't be afraid. Fear turns us into accomplices and prisoners of violence. Today I stand before you to plead for your courage."

Some survivors and relatives of those dead and injured in the September 15, 2008, grenade blasts attended the 2009 commemoration in Plaza Melchor Ocampo.

She begged the relatives of last year's injured and deceased, "Hold out your dead like a flag of struggle for the well-being of all. Forgive the attackers, involve yourselves in the search for liberty."

Children from a few specially selected schools attended the commemorati

ve event.

At the end of the ceremony–where seating was limited to 1000 people

and standing room was at the very edge of the plaza, behind a security

barricade–Rigoberta Menchú called out once again for peace. "From

Morelia, we celebrate peace, life, and dignity. In the struggle for

peace, we all have something to give. The amount of material things we

can offer isn't important. What is important is our struggle for the

common good."

A strong military presence at the event seemed to contradict Rigoberta Menchú's plea for peace.

Morelia's Municipal Tourism Secretary Roberto Monroy noted that the government invited Rigoberta Menchú so that her presence in Morelia could be seen as a message of peace, of cordiality, and a sign that the capital and the state of Michoacán are still standing, working for the development of peace.

Several of Mexico's Federal police helicopters circled and circled the Centro Histórico after the event.

Despite the contradictions between Sra. Menchú's compelling speech and the military actions of the government, the event left Mexico Cooks! with the joy of seeing and hearing a woman struggling tirelessly on behalf of peace. There are so few like her in today's world: committed, valiant, single-minded in the search for peace. Qué viva Rigoberta! Qué viva!

Picasso's Dove of Peace is still a sign hope for the future of Mexico and the world.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.