On July 22, 2010, UNESCO awarded Mexico's ancient corn-based cuisines–in particular the traditional cuisine of Michoacán–with the very first coveted World Heritage designation granted to a cuisine: Patrimonio Intangible de la Humanidad. Dra. Gloria López Morales, head of Mexico's Conservatorio de Gastronomia Mexicana, made the announcement in Bogotá, Colombia, where she was attending a culinary conference organized by that country's Mexican embassy. After six years of concerted efforts by Dra. Morales and many others involved in the preservation of Mexico's rich culinary history, the award brings honor to our beloved country and her exquisite traditional kitchen.

This article, originally published by Mexico Cooks! on June 14, 2008, offers a brief overview and a bit of insight into Mexico's history of corn and its uses.

Yumil Kaxob, the Mayan corn god.

Mexico is corn, corn is Mexico. From prehistoric times, Mexico has produced corn to feed its people. Archaeological remains of early corn ears found in the Oaxaca Valley date as far back as 3450 B.C. Ears found in a cave in Puebla date to 2750 B.C.

Diego Rivera, Festival de Maíz, 1923-24.

Around 1500 B.C. the first evidence of large-scale land clearing for milpas appears. Indian farmers still grow corn in a milpa, (corn field), planting a dozen crops together, including corn, melon, tomatoes, sweet potato, and varieties of squash and beans. Some of these plants lack nutrients which others have in abundance, resulting in a powerful, self-sustaining symbiosis between all plants grown in the milpa. The milpa is therefore seen by some as one of the most successful human inventions – alongside corn.1

Listen as this group from Burgos, Tamaulipas, sings a song from the early 20th Century: Las Cuatro Milpas. The song's sad verses recount the loss of a family's home and its milpas.

"Only four cornfields remain

Of the little ranch that was mine,

And that little house, so white and beautiful

Look how sad it is!

Loan me your eyes, my brown woman,

I'll carry them in my soul,

And what do they see over there?

The wreckage of that little house,

So white and beautiful–

It's so sad! The stables no longer shelter cattle,

Everything is finished! Oh, Oh!

Now there are no pigeons, no fragrant herbs,

Everything is finished!

Four cornfields that I loved so much,

My mother took care of them, Oh!

If you could just see how lonely it is,

Now there are no poppies and no herbs!"

The family-owned milpa is quickly disappearing from Mexico's flatlands and hillsides, giving way to agro-business corn farming. Today, Mexico's corn industry produces more than 24 million tons of white corn a year. Nearly half again that amount is imported from other countries. The imports are primarily yellow corn used to feed animals.

Woman singing to or praying over corn as she puts it in the fire– so that the corn will not be afraid of the heat. Florentine Codex, Fray Bernardino Sahagún, third quarter 16th Century.

According to the Popul Vuh, the Mayan creation story, humans were created from corn. Do you know the story?

At first, there were only the sky and the sea. There was not one bird, not one animal. There was not one mountain. The sky and the sea were alone with the Maker. There was no one to praise the Maker's names, there was no one to praise the Maker's glory.

Traditional milpa (cornfield) in the mountains of central Mexico.

The Maker said the word, "Earth," and the earth rose, like a mist from the sea. The Maker only thought of it, and there it was.

The Maker thought of mountains, and great mountains came. The Maker thought of trees, and trees grew on the land.

The Maker made the animals, the birds, and all the many creatures of the Earth.

Masa tricolor (three-color corn dough) ground by hand using the metate y mano.

The Maker wanted a being in his likeness. First the Maker used dirt to create a Human, but

made of mud and earth. It didn't look very good. Dry, it crumbled and wet, it softened. It looked lopsided and twisted. It only spoke nonsense. It could not multiply. So the Maker tried again.

Our Grandfather and Our Grandmother, the wise deities of the Sun and Moon, were summoned. "Determine if we should carve people from wood," commanded the Maker.

They answered, "It is good to make your people with wood. They will speak your name.

They will walk about and multiply."

"So be it," replied the Maker. And as the words were spoken, it was done. The doll-people were made with faces carved from wood. They had children. But they had no blood, no sweat. They had nothing in their minds. They had no respect for the Maker or the creations of the Maker. They just walked about, accomplishing nothing.

"This is not what I had in mind," said the Maker, and destroyed the wooden people.

In Michoacán, unfilled tamales called corundas are eaten with churipo, a richly delicious beef and cabbage soup.

The Maker sat and contemplated the ears of corn, the kernels of the ears. The Maker thought, "What comes from this nourishing life will be my people," and the Maker ground the corn, ground the corn and formed Man and Woman. On the first day, when Man and Woman, formed from corn, awakened, they rose up praising the Maker's name and giving thanks for their lives. They bore children, they praised the Maker as they planted corn and tended the crop. They were made in the Maker's image, born from corn. The Maker and his people rejoiced in one another."

Stone image of Yumil Kaxob. Photo courtesy of Michael Martin.2

Imagine an entire people formed from corn, formed to honor the seed, the earth, the plant, the crop! Corn cannot grow without human intervention; ancient Mesoamerican humanity could not have existed without corn. Spiritual planting rituals continue to be celebrated in the milpas every chosen planting day.

Corn is still the staple food of Mexico. Nixtamal (dried dent corn soaked in water and cal, builder's lime) is corn's basic currency. Nixtamal is the starting point for the tortilla, the tamal, the corunda, the sope, the cup of atole, and a myriad of other masa-based preparations.

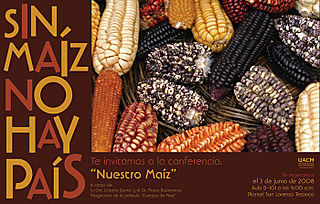

This poster advertises a conference about "Nuestro Maíz" (Our Corn) held on June 3, 2008 at the Autonomous University of Chihuahua, Mexico.

As Mexico changes, corn production also changes. NAFTA and globalization have affected Mexico's corn industry, as has genetic modification of corn itself. Is corn food, or is corn fuel for vehicles? Argument rages about the future of Mexico's corn. There is, however, no doubt: sin maíz, no hay país. Without corn, there is no country.

1. http://www.philipcoppens.com/maize.html

2. http://www.pbase.com/pinemikey/image/85632845

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.