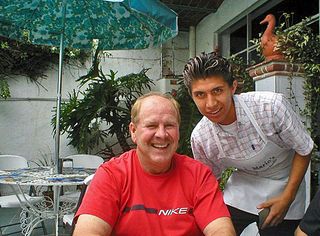

My dear friend Darrell Schmidt (left) with Eric Enciso Cárdenas, who for several years was part of his father's wait staff at Restaurante Mario's at Lake Chapala. Eric was probably sixteen years old in this snapshot. Photo courtesy Jackie Shanks.

A few weeks ago, it was Mexico Cooks!' enormous pleasure to dine at a golf ball driving range. "A what?" you might well ask. "What did you eat, hot dogs on a roller-grill?" Oddly enough, the Hole in One driving range has become the hot spot for superb food at Lake Chapala. Even odder, the exciting and innovative chef is a young local man whom I've known since he was ten years old.

The two faces of the Hole in One: fine dining combined with a driving range. Makes perfect sense to me. Photo courtesy THIS.

Eric grew up in a restaurant family. His father, my camarada Jaime Enciso, is head of the wait staff at Restaurante Mario's in San Antonio Tlayacapan, one of the small towns strung like beads along the north shore of Lake Chapala. His mother, Alicia Cárdenas, is the pastry cook for the same restaurant and a caterer in her own right. Eric hung at out the restaurant from the time he was no taller than the tables, and started working as a waiter when he was about eight or nine years old. Nevertheless, when asked what he wanted to be when he grew up, the answer was always, "A doctor."

Looking north toward the mountains from the Hole in One. Photo courtesy THIS.

As the saying goes, life is what happens while you're making other plans. Eric's mother wanted something different for him. She suggested that he try culinary school instead of medical school. Eric balked, but he gave in and after finishing high school, he was accepted by the Universidad de la Ciénega in Guadalajara to study a four-year licenciatura en gastronomía (similar to a bachelor's degree). "At first I didn't like it at all," Eric said. "It was just book study about things that didn't really interest me, like nutrition and history. I didn't think it had anything to do with cooking or with me. I stayed with it, though, even though I was bored."

Crema de elote al tequila terminada con reducción de pétalos de rosa (cream of corn and tequila soup with a swirl of rose petal reduction), on the September 20, 2010 Hole in One evening menu. Photo by Mexico Cooks!.

After about a year of study, Eric was seriously injured, run over by a car in Guadalajara. During the six months he spent in bed following the accident, he continued to study his books. When he was finally able to return to the university classrooms, he said, "I really threw myself into it. Something had changed.

"I was in school in Guadalajara from mid-afternoon till late evening every day, but I was still driving back and forth and living at home here at the lake. I needed to work at night to help with my expenses, so I went to the restaurant called Number Four [in Ajijic, another of the Lake Chapala north shore towns] to see if they needed any help. The chef there asked me a lot of questions and decided that I knew absolutely nothing about cooking. He was right."

Ensalada de conejo salteado al ajo, lechugas orgánicas, fresas, pitahaya y nueces con una vinagreta de vinagre balsámico (salad with rabbit sautéed in garlic with a mix of organic lettuces, strawberries, dragon fruit, and nuts in balsamic vinegar dressing. Photo by Mexico Cooks!.

"In spite of my not knowing anything about preparing food, the chef offered me a huge break. He gave me hands-on lessons in everything. The first thing we did was line up all the fresh herbs he used, from cilantro and epazote to basil, oregano, parsley and rosemary, and he made me memorize how they looked, how they smelled, and how they tasted. When I knew those things, he started with spices: curry, ginger, allspice, nutmeg, everything! Which is this one, which is that one! It was an entire hands-on education that put me far ahead of my schoolmates, who were still studying just from books.

Rack de cordero con jalea de menta servido sobre puré de papa perfumado de trufa y ejotes franceses salteados (rack of four lamb ribs, grilled with select herbs, served over truffle-scented mashed potatoes and sautéed French green beans. With mint jelly. This main dish was perfectly prepared, beautifully presented, and entirely memorable. Photo by Mexico Cooks!.

"So many wonderful opportunities have been offered to me. I worked with every extraordinary chef who passed through the kitchen at Number Four, and I learned from them to prepare exotic cuisines of many countries. When I finished my licenciatura, I had much more real-life restaurant experience than the other members of my generación (graduating class). And most important, I realized that I was truly meant to be a chef. Every day is an adventure in taste, in innovation, in preparing something to widen your eyes and your horizon of what food can be.

Rib-eye "Premium Beef" marinado en romero y ajo, a la parilla con salsa de cebolla-Nebiollo, servido sobre puré de papa al parmesano, espárragos, y col Bruselas salteados (ribeye marinated in rosemary and garlic, grilled and served with red wine onion reduction, served over Parmesan mashed potatoes, sautéed asparagus spears, and Brussels sprouts. I thought this was the least successful dish of the evening and even it was delicious. Photo by Mexico Cooks!.

"I love to experiment, love to bring new touches to traditional cuisines. For example, the restaurant just offered a two-night special event in honor of Mexico's 2010 Bicentennial. The menu was completely de vanguardia y de autor (avant garde and the chef's personal creations), but everything was prepared with traditional Mexican ingredients. My assistants and I prepared the crema de elote that you just ate, a tamal filled with rabbit and huitlacoche (black corn fungus) and bathed with yellow mole, a local-ingredients salad, fish rolled with hoja santa with two salsas, locally-grown quail stuffed with figs, plums, and pumpkin seeds in a hibiscus-chile sauce, and pork medallions stuffed with requesón (a cheese similar to ricotta), huauzontle (a green vegetable), hoja santa, and other totally traditional pre-Hispanic herbs served in a sauce made of sour cactus fruit and agave syrup.

"Few of the foreigners who ate here during the Bicentennial fiestas knew what they were eating, since most of them are only familiar with standard Mexican fare like tacos and enchiladas. But the nearly 600 people who ate our food on those two nights asked so many questions about the delicious things they tasted–'what is this, why did you use that, where does this come from'–and they loved it all. Best of all, they went away with a different appreciation of what Mexican food can be. Obviously this is not comida casera (home cooking). Instead, it's the first time real alta cocina mexicana (Mexican haute cuisine) has been offered here at Lake Chapala.

Granita Hole in One: duo de guanábana y tuna morada con vino Zinfandel (two sorbets, one of soursop (right) and the other of purple cactus fruit with Zinfandel). Photo by Mexico Cooks!.

"The most important thing to me is to take my cooking from the base of Mexico's traditional ingredients. The foods that were here thousands of years before the Spanish arrived have mixed with Spanish, French, and Asian influences since the 16th Century. It's tremendously exciting to me to be a young chef in this epoch, bringing my own ideas into the context of existing cuisine. I can hardly wait to get into the kitchen every workday."

Creme brulée flavored with lemon grass and vanilla, served with locally grown blackberries. Photo by Mexico Cooks!.

And what does Mexico Cooks! think about this young chef? If you live at Lake Chapala, if you are anywhere in that vicinity, if you are planning a trip to Guadalajara, GO!–hurry to experience Chef Eric Enciso Cárdenas while he is still in the kitchen at the Hole in One. It won't be long before someone from a more elegant room in a bigger city steals him away. His culinary genius and his incredible joy in his profession make him my pick for who to watch in the Mexican kitchen in 2011.

Mark my words, world.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.