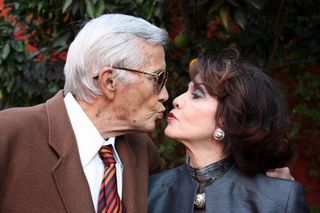

The delicious Betsy Pecanins captured Morelia's heart in October 2010.

Betsy Pecanins opened her recent Morelia concert with a song that frankly states, "I am my voice." This tiny woman's songs filled Morelia's 1200-seat Teatro Morelos with her heart, her warmth, and her personal charisma, giving the large audience exactly what they wanted: Betsy! Betsy! and more Betsy! Fresh from an open-air concert in Monterrey, Nuevo León, she sang her trademark gutsy blues, some contemporary Mexican songs–and, in her particular and much-loved style, bluesy interpretations of Mexican ranchera favorites–to an enamored crowd of Michoacanos.

Betsy belts one, accompanied by her drummer, Héctor Aguilar and the extraordinary harmonica player, Jorge Follado.

Like several of Mexico's other adored women singers (Rocío Dúrcal, Tania Libertad, and Chavela Vargas, to name just three), Betsy Pecanins is not originally from Mexico. Born in Yuma, Arizona, she says, "I'm embarrassed to say that I come from there, given the current situation in Arizona." Child of an American father and a Spanish mother, Betsy grew up in that hotter-than-hell border town. In her teens, she moved to Mexico City to live with her father and his family. "It was really hard in a lot of ways," she admitted. "I didn't speak Spanish, and I didn't like the food. It took me a while to get accustomed to life here, but as you can see, I did." Pecanins now considers Mexico to be her home of choice, and, after more than 30 years here, she speaks fluently colloquial Spanish.

Cellist Mónica del Águila and bassist Alfonso Rosas deepened and enriched the evening's music. Notice the electric cello!

Pecanins is touring in Mexico to promote her latest recording, titled Sones y Pasones. "It was really difficult to choose which songs from the CD to bring to the concert. Of course I love them all, but finally we chose 16 to offer on stage." Unless you know her style, you might find it hard to reconcile Mexico's sones and huastecos with the down-and-dirty blues of Willie Dixon. The two Mexican musical styles, which incorporate indigenous, gypsy, Spanish, and African rhythms, combine like magic with Pecanins-style blues.

Betsy happily applauds her fans, who spent the evening cheering in appreciation for her concert.

The evening before the concert, Betsy chatted with Mexico Cooks! about her long tenure in Mexico. "Like everyone else, I'm worried about the violent troubles we're living through right now. Like everyone else, I don't really see an immediate solution. But I also believe that we just have to go about our daily business and not live in fear. What good would it do, what would it serve, to hide and forget to live our lives? That would mean that organized crime wins, and that the good people of this country lose. Obviously we all have to be careful, but we can't forget the joy of living. So yes, I'm touring. It was important to me to sing in Monterrey, where the people have lived through so much sorrow. And it's important to me to sing in Morelia."

La Pecanins, shouting the low-down blues: Willie Dixon's "29 Ways (To Get to My Baby's Door)". Listen here to another interpretation: 29 Ways.

Betsy is a true original, combining musical roots of several cultures and eras to create a unique sound. She's been a bright light in the Mexico City musical scene for more than 30 years; during that time, she has recorded sixteen very well received CDs. She brings her sense of place, her sense of time, and her sense of humor to the stage along with her voice. Before singing "Aquí Me Ves", she offered the story of an old love, a flame that burned for two years when she was 20. Thanks to the wonders of the Internet, the old flame found her again online. And she got nervous: "I'm not the same as I was when I was twenty," she said, gesturing from her shoulders to her knees. "Certain things fall–for women, and for men, too! But my friend Rafael Mendoza wrote this song for me, a song that says, 'I may not be the same person I was back then, but I'm much more of a woman.' It's so true!" Nevertheless, she laughed, "Unfortunately, things didn't work out between me and him–but I still have the song!"

Betsy and harmonicist Jorge Follado cue up a solo by the band's acoustic guitarist, Jorge García.

The concert was presented as part of the October celebrations of the anniversary of the founding of Morelia's Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo (UMSNH). In addition to Betsy's concert, the university also presented a three-week repertoire of other cultural activities.

Betsy with her pink kazoo. Hearing the buzz of that kazoo took me back to my own roots in folk music, more years ago than I care to confess.

Betsy is currently undergoing treatment for vocal difficulties that affect her ability to speak much more than her ability to sing. Her vibrant new CD, Sones y Pasones, is terrific evidence that her quest for meaningful fusion between musical styles is a huge success. If she's appearing anywhere near your city or town, go hear her. You'll fall under her spell, just as we did here in Morelia.

The band takes a final bow after its concert in Morelia. Left to right: Héctor Águilar, Mónica del Águila, Alfonso Rosas, Betsy, Jorge Follado, and Jorge García. After Betsy congratulated each of the band members by name at the concert's end, the entire band leaped up and down shouting, "Betsy Pecanins! Betsy Pecanins! Betsy Pecanins!"

All photos and written material copyright Mexico Cooks!.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.