Pan Segura, Legítimo Estilo Jalisco (Bread Segura, Real Jalisco Style) is almost literally a hole in the wall on Calle 16 de septiembre in Mexico City's Centro Histórico. There's just enough open space for a person to squeeze single file and sideways past a bread case and into the slightly wider part of the bakery to pick up a tray and tongs. Buy bread here often enough and you probably won't fit through the door!

A few weeks ago, Mexico Cooks! received an email from a total stranger: Jane Mason, the owner of Virtuous Bread, asked me where to buy certain kinds of specialty flours in Mexico City or anywhere in the rest of the República. Originally based in England, Jane Mason has recently been working on a bread-baking project in the Distrito Federal. After exchanging several notes with me, she mentioned that she and her partner were taking a Centro Histórico tour of traditional bakeries that weekend. Would I like to join them? Did I leap at the chance? You bet!

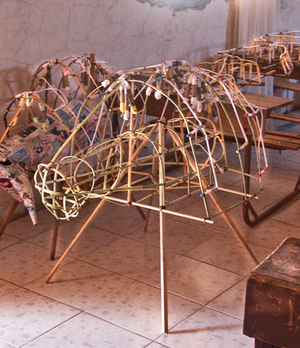

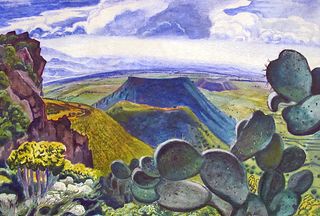

Racks of Jalisco-style pan dulce (Mexican sweet breads) at Pan Segura. Their most famous sweet bread is the unique cuadros de queso (cheese squares). Large, densely textured, and completely delicious, the bread balances between sweet and salty. With a freshly squeezed glass of juice, it's big enough to be breakfast. It's also addictive. Trust me, eating one cuadro de queso today leaves you wanting another tomorrow.

Universidad Iberoamericana, in the person of Maestra Sandra Llamas, planned the bakery tour to explore the 19th century presence in Mexico of Basque immigrants from the province of Navarre, Spain. Those immigrants came from the Spanish Valley of Baztán to live in Mexico City at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries. Ultimately, they became the most important European influence on Mexico's commercial bakeries, flour sellers, and yeast purveyors.

Maestra Sandra Llamas begins the tour of traditional bakeries by offering an overview of prominent Basque bakers in 19th century Mexico City. Approximately 25 people of every young-adult and adult age participated in our three-bakery walking tour.

During Porfirio Díaz's long presidency/dictatorship (1876-1910), all things European were very much the rage in Mexico. Spanish and French goods were much more highly valued than goods made in Mexico. During the Porfiriato (the name used to describe those nearly 35 years), many Basque families were accustomed to sending their adolescent first-born sons to the New World. These young men arrived all but penniless in Mexico, and their families in Spain expected that they would make successes of themselves in their new homes.

In 1877, there were 68 bakeries in Mexico City. By 1898, the bakery count was up to 200. Most of the bakery owners were Basques from Navarre. They did not bring baking to Mexico, but they did bring a particular way of doing business. They bought wheat fields, built urban rather than rural flour mills, bought bakeries, and soon dominated the market that catered to one of humankind's basic needs: hunger.

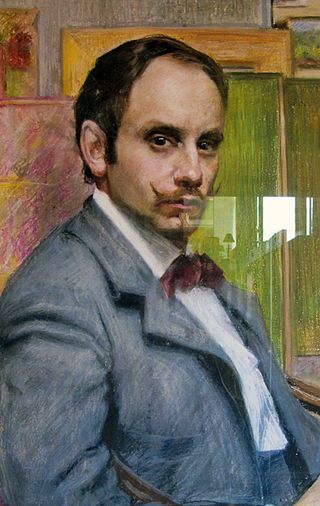

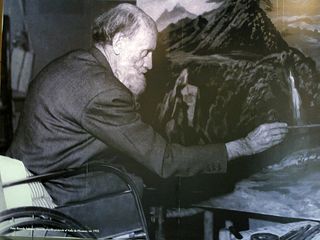

Don Braulio Iriarte Goyeneche was born in Navarra, Spain, in 1860 and arrived in Mexico City in 1877.

Arguably the most successful of these young Basques was the teenager who, as an adult in Mexico City, would be known as don Braulio Iriarte Goyeneche. In 1877, his family forced him to leave Navarra and make a life for himself in this unknown world across the sea. Industrious, hard-working, and creative, the young Iriarte began his career as an employee at one of Mexico's first commercial bakeries. By the end of the 1800s, he was Mexico's king of flour, yeast, and bread. The two keys to his success were his business acumen and the trustworthy cleanliness of his bakeries.

Jalisco-style bread from Pan Segura. This tiny bakery has been in operation for 85 years.

During the fourth quarter of the 19th century, common practice meant that campesinos (country boys) worked barefoot in bakeries. In an attempt to keep their feet clean, they were not allowed to go outside the bakery during the day–locked in with the ovens, barefoot boys and young men clad in the white pants and shirts of the campesino, danced 17 hours a day in the heat of a wood-fired bakery to knead the fresh-made dough . It's no wonder that some customers complained occasionally that their bread was too salty: blame the extra salt on the campesinos' sweat blended into the flour mixture. Don Braulio's bakeries were considered to be extremely sanitary because, unlike in other Mexico City bakeries, machinery did all the kneading. No one's feet touched the dough.

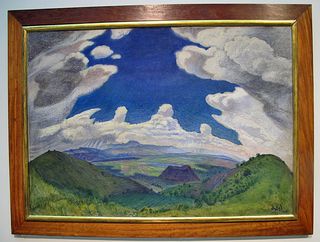

Conchas (shells, a kind of sweet bread) from Panadería El Molino. These conchas are quiet large, and you can see that the price per piece is five pesos (at today's exchange rate, approximately 36 US cents).

At the end of the 19th century in Mexico, the salary for a Mexico City panadero (baker) was two pesos per month. Yes, two. In 1903, Mexico City's bakers began what is known as la huelga de los bolillos (the bread strike). Their demand? A raise in salary to 2.5 pesos per month. The bakers gave or threw away thousands of the individual loaves of white bread known as bolillos to protest the bakery owners' reluctance to pay them a half peso more per month. The bakery owners' main fear was that their young men would drink substantially more due to the salary increase.

Sr. Iriarte rapidly rose to the highest level of prominence in Mexico's world of wheat, flour, and yeast. Within 30 years of his arrival in Mexico City, he and a business partner owned numerous bakeries, had opened a flour mill in Toluca (near the urban center of Mexico City), and founded Mexico's first commercial yeast factory. By the end of the 1920s, he was grinding nearly all of Mexico's wheat.

In early 1922, Sr. Iriarte added another business to his stable: the Corona brewery, which has grown to become one of the largest and most important breweries in the world. Its flagship beer, Corona, is the largest-selling Mexican beer in the world. What's the connection between beer and bread? Yeast.

At El Molino, a bakery worker paints apricot syrup onto fresh-from-the-oven trenzas (braids) made of puff paste. She will then sprinkle the braids with sesame seeds.

You don't use your fingers to pick up bread in Mexico's bakeries. Near the entrance to any bakery, you'll find trays and tongs for choosing what you want to buy. The check-out clerk will use your tongs to put your bread in its bag or box, then bang the crumbs off the tray and back it goes for the next customer's use.

Our tour took in three bakeries, all within a few blocks on Calle 16 de septiembre in Mexico City's Centro Histórico. Pan Segura is the smallest of the three, barely big enough for four or five people to shop for bread at the same time. Pastelería El Molino, just down the street, has been in business since 1918 and was purchased first by Carlos Slim Helú's Panadería El Globo and then was sold to Grupo Bimbo, a giant international wholesale bread-baking concern which bought both bakeries in 2005.

One small room on the first floor of Pastelería La Ideal.

Cochinitos (gingerbread pigs), detail of one tray with stacks and stacks of one of the most traditional sweet breads in Mexico, Pastelería La Ideal. The number of trays of cochinitos is beyond comprehension. Seeing is almost–almost!–believing.

Little cookie men in their two-button suits at La Ideal.

The crown of our bakery tour was its visit to Pastelería La Ideal, long one of Mexico Cooks!' favorite spots in Mexico City. The bakery is enormous. Founded in 1927, the bakery specializes in…well, it specializes in being special. The first floor is devoted to decorative and delicious gelatins, flans, small cookies called pasta seca, everyday cakes, and breads. Hundreds of kinds of breads–350 different kinds, to be exact. Unbelievable amounts of bread, but there it is: right in front of your eyes and absolutely believable. This bakery alone (it has two more branches in the city) turns out 50 to 55 thousand pieces of bread every day, seven days a week.

Muffins with candied fruits, Pastelería La Ideal.

This branch of Pastelería La Ideal is closed for cleaning for exactly one hour a day. If you go between five and six o'clock in the morning, you'll find the doors locked. Otherwise, teams of master bakers (17 to 20 per shift, three eight-hour shifts per day) supervise and work with 350 workers to give us this day our daily bread.

La Ideal traditional package on Mexico Cooks!' dining room table. We bought our neighbor a coffee cake. Honest, it was for her, not for us.

During the early morning hours, you'll see men and women rushing up and down Calle 16 de septiembre and its surrounding streets, carrying packages from La Ideal, tied up with string, tucked under their arms or dangling from outstretched fingers. Mexico City's desayuno (breakfast), whether at home or at the office, almost always includes a pan, either salado or dulce (salty or sweet bread). Cuernitos (like croissants), biscoches (biscuits), panqué (poundcake), pan danés (Danish pastry), bigotes (bread shaped a bit like a moustache), orejas (elephant ears), and conchas (shells), plus bolillo, telera, and all the other kinds of breads fly off the shelves and into Mexico City kitchens, to be served with a coffee or hot chocolate.

Chocolate cake filled with strawberry marmalade and topped with cream horns, Pastelería La Ideal. In the evening, Mexico City stops back in at La Ideal to buy a little something for cena (light supper): a cake, a gelatin, or some cupcakes or cookies. This cake costs 190 pesos. Click on any photo to enlarge and show details.

The second floor of Pastelería La Ideal is entirely about big-deal party cakes. You and the person who is giving a party with you sit down at a tiny desk with a La Ideal sales associate to have a serious discussion about cake: how many people you plan to invite, how much other food there will be, what the occasion might be, how much you want to spend, and any other question you need to ask to have just the right cake made for your needs.

This six-kilo cake (model J-28) decorated with a chocolate basket and pink sugar roses would be perfect for your aunt's birthday, Mother's Day, or any occasion where a small cake is necessary. Hold onto your hats:

Model L-20, decorated with clowns, balloons, ribbons, and stalactites made of icing, weighs 25 kilos and is designed for a child's birthday party. Twenty-five kilos and four stories equal a mid-size cake at La Ideal. There are cakes for quinceañeras (girls' fifteenth birthday parties), engagement parties, first communion parties, and wedding receptions that weigh as much as 50 kilos or more. Those cakes are constructed with stories, bridges, and some have actual running-water waterfalls. The size of your expected crowd dictates the size of the cake.

Some things at your bakery are just about the same as they were when the Basques came to Mexico: bread is freshly baked throughout the day and night, it's affordable, and some is still quite delicious. Other things have changed completely: in most commercial bakeries, margarine or vegetable shortenings are used instead of butter, most everything is mechanized, and the lowly, delicious bolillo–Mexico's original white bread–is now more like cotton batting than like honest bread. But Jane Mason of Virtuous Bread and Mexico Cooks! have vowed to track down any real bolillo that still exists. It's the best thing since–since before sliced bread! I promise to report back.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.