This weaver, using a back strap loom, creates a patterned fabric by counting threads.

Twenty to thirty thousand years ago, early humans developed the first string, made with handfuls of plant fibers: they discovered that preparing thin bundles of plant material and stretching them out while twisting them together produced a fine thread. The ability to produce string and thread was the starting place for the development of spinning, weaving, and sewing. All three of those indigenous textile making traditions are still strong in today's Mexico.

The fundamental aspects of hand weaving have remained unchanged for millennia. Webster defines a loom as "a frame or machine for interweaving yarn or threads into a fabric, the operation being performed by laying lengthwise a series called the warp and weaving in across this warp other threads called the weft, woof, or filling." Another definition, quite to the point, states: "A loom is the framework across which threads are stretched for the weaving of cloth."

Using a back strap loom in Zinacantán, Chiapas. Mexico Cooks!, 2008. Click on any photo for a larger view.

When the back strap loom was developed, it was easy to transport and simple to construct. One end of the loom was attached to a fixed point, like a tree trunk, and the other was a rod, which was held in place with a cord that passed around the waist of the weaver. By leaning back against the waist cord, the weaver could put tension on the warp threads and adjust tautness at will. The back strap loom is still used today by Native Americans in the southwestern part of the United States and by people in Central America and Mexico. The complexity of the work that can be created on this loom is limited only by the skill of the weaver, and the entire loom with the weaving in progress can be rolled up at any time and carried from place to place.

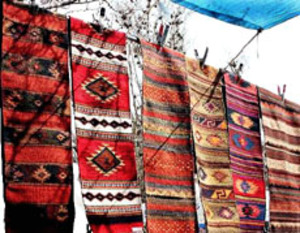

Hanks of naturally dyed wool, drying in the sun in Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca.

In the culture of Mesoamerica (the region extending south and east from central Mexico to include parts of Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and Nicaragua), clothing fabrics were quite diverse. In arid locations, plants such as yucca, agave cactus, and palm fibers were used for weaving. Where the climate permitted its cultivation, cotton was the chosen fiber. Cotton was grown in Mexico as early as 3000 B.C.–more than 5000 years ago. Although cotton did not grow in the central region of the Aztec empire, the Aztecs obtained cotton from the peoples they conquered. At that time, only certain social classes were allowed to wear cotton clothing. Rabbit fur and feathers from exotic birds were woven into fabric to decorate luxurious clothing, while amate (bark paper) clothing was used for some ceremonial vestments. The clothing of lower social classes was made of much rougher fibers.

Everywhere in Mesoamerica, women wove using a back strap loom, and then sometimes embroidered fabrics and applied shells, precious stones, and silver and gold ornaments to the fabrics they wove. In the south of Mexico, women made weavings using ornamental stitches or, among the Maya, decorating fabric with thin braided ropes.

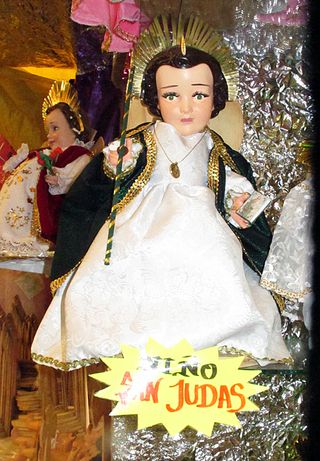

Fabrics woven in those ways were of the highest importance in early Mexican life. At times, fabrics were used as money. Each culture of Mesoamerica had deities who watched over those women who carded wool, spun thread, those who wove, and those who embroidered. At birth, a baby girl was symbolically initiated into the work of weaving, and upon her death, a woman was buried with the textile tools that she had used all through her life. Textile making was considered to be much more than a technique. It was a sacred gift bestowed on women by the gods.

Seeds and other plant material are used to make natural dyes. The basket on the right holds a wooden spindle and a hand carder for raw wool.

Conquest by the Spanish and the continuing presence of the conquistadores changed the panorama of textiles in Mexico. During the time of colonization, new techniques of weaving, materials, designs and forms of dress arrived in the what was then called New Spain. Silks, wools, and the pedal loom needed to weave them were introduced. In addition, the Spanish brought a strong textile influence from Asia and Egypt.

The richness, variety and liveliness of Mexican weaving are in large part derived from the fusion of these influences. Traditional Mexican indigenous clothing represents the union of the people, proud of their geographic and cultural origins.

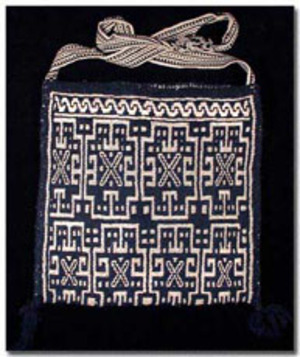

In the February-March 2005 New Life Journal, author Lisa Lichtig wrote, "For women, the loom is the violin. Woven bags come in various sizes and colors and are used for carrying everything from food to sacred offerings. Each, however, is made with special woven designs that are signatures from the heart and the dreams of the weaver.

"In the process of learning to weave, the apprentice makes miniature weavings as offerings to the gods. When a girl leaves her offering, she may take one of the offerings left for that same god by another girl or woman. She takes the borrowed offering home and copies the design, and then returns the borrowed piece and leaves another one that she herself has made. This practice has been a means by which designs were distributed among Huichol women."

When the Spanish came to the New World, they brought sheep, previously unknown to the indigenous peoples of Mexico. The natives quickly learned to shear, card, spin, and weave wool. They used native vegetable and mineral dyes to create the vibrant colors so crucial to their designs. Today, as indigenous people herd fewer and fewer sheep, acrylics have largely replaced wool in woven work. Very few weavers still know how to make and use the old dyes.

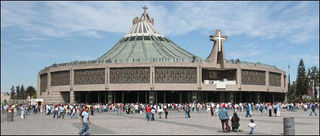

The indigenous Zapotec are native to the state of Oaxaca, in southernmost Mexico. Many Zapotec are extraordinary rug weavers. The most famous Zapotec rug weaving center is Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca, a remote mountain village that has become well known everywhere in the world due to the traditional fine weaving done there. Despite its remote location, the world shows up on the doorsteps of Teotitlán del Valle to buy from the weavers. Rugs from the village are sold all over Mexico as well as in the United States and other countries.

Detail of a rueca (spinning wheel) in Teotitlán del Valle.

Before the arrival of the Spanish and their sheep, the Zapotecos had been cultivating and weaving cotton for several thousand years. Like the Huicholes, the Zapotecos quickly learned to card, spin, dye, and weave wool. They have used traditional vegetable and mineral dyes for centuries, although aniline (artificial) dyes came into use about 30 years ago.

The secrets of natural dyes are jealously guarded. They are extracted from a range of plant mineral and insect sources: indigo blue from the jiquilete plant, green from malachite copper, and the vibrant hues of the red from the world famous cochineal scale insect which lives on the nopal cactus. Dyes are hand-ground and hand mixed.

Buyer's Note: Some of Mexico's weavers have begun using artificial dyes due to the difficulty and expense of creating dyes with flowers, herbs, insects, and other natural materials. Ask your rug dealer which dyes he uses. Discerning buyers and collectors insist on natural dyes. Be aware that if a dealer claims to use only natural dyes and the price of a rug you like seems too good to be true, his or her claim is probably not true.

The Zapotec weavers of Teotitlán wove only on traditional back strap looms until the Dominican missionaries introduced harness looms in the 16th Century. Today, some Zapotec weavers like to create modern carpet designs based on the art of Diego Rivera, Pablo Picasso, or Max Escher. Others disagree. One weaver said, "Those are beautiful designs, but those designs are created by painters. I am a weaver, and my rugs are the traditional designs of my people."

Wool rugs from Teotitlán del Valle, if properly cared for, will last a lifetime whether you use them on your floors or hang them on your walls. Mexico Cooks! would be delighted to take you to Teotitlán to meet the weavers.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.