The tiny storefront with the hand-lettered sign reading Joaquinita Chocolate Supremo is at Calle Enseñanza #38 in Pátzcuaro, Michoacán.

In Pátzcuaro, the tradition of chocolate de metate (stone-ground chocolate) is still alive, personified by Sra. María Guadalupe García López. Doña Lupe, as she is called by everyone who knows her, continues the work started in Pátzcuaro in 1898. The family recipe for chocolate de metate was left to her as a legacy by her mother-in-law. Rightly proud of her hand-ground chocolate, Doña Lupe said, "I'm convinced that by now, just about everyone in the whole world knows about chocolate de metate, and everyone who tastes it falls in love with it."

Costales (huge burlap bags) of raw cocoa beans from the state of Tabasco. Doña Lupe stores the costales in a cool spot in her sótano (basement).

In Pátzcuaro, there are several home-based businesses which make chocolate that claims to be made on the metate, but its preparation and commercialization are not authentic. Doña Lupe says that Joaquinita Chocolate has no locations other than her home. "Some of the chocolate makers here in town claim to be my children or my grandchildren, but they're not. They're not part of Joaquinita Chocolate." Joaquinita Chocolate is not only the best known, but is also completely traditional in its preparation.

From the sidewalk, the house is unprepossessing. It looks like most houses in the central part of Pátzcuaro: painted white, with a deep, ochre-red base. But come closer, step up to the door: you'll be stopped in your tracks by the rich fragrance of home-made chocolate. Breathe. Walk in. You'll never learn the jealously guarded secret of Doña Lupe's recipe, but you'll taste one of the legendary treats of Mexico's past and present.

Lovely Doña Lupe is ready to drop a tablet of her chocolate semiamargo (semisweet) into a pitcher of near-boiling water, just as in the novel and film "Like Water for Chocolate". The molinillo (hand-carved wooden chocolate beater) whips the melted chocolate into a thick froth and it's ready to serve.

Chocolate was unknown to Spain and to the rest of Europe in 1519, when Cortés arrived on the shores of the New World. Moctezuma and the highly-placed leaders in his court knew its subtleties; Cortés was soon initiated into its delights. Mixed with vanilla and other spices including chile, xocolatl (shoh-coh-LAH-tl) needed to be mixed with water and beaten to a heavy froth before being consumed unsweetened. Europeans quickly discovered that a bit of sugar took away the bitterness and enhanced the flavors of the new drink. Before long, chocolate was the rage of Europe as well as a near-addiction for Europeans in the New World.

The process of making chocolate estilo Doña Lupe (Doña Lupe-style chocolate) starts with the finest beans from the state of Tabasco, in southern Mexico. Doña Lupe says that the seed (what we usually call the cocoa bean) has to be the best, or else the chocolate loses its texture and its flavor. She won't use a lesser bean.

Toasting cocoa beans over a wood fire requires constant stirring. The fogón is shaped like a horseshoe to accommodate the cazuela.

While the carbón (natural wood charcoal) heated on the fogón (raised fire ring), Doña Lupe talked about making chocolate de metate. "First we take as many beans from the costal (large bag) as we need for the day. Normally, I make 20 to 30 kilos of chocolate tablets every day.

"Next I clean the beans, taking out any small stones, any leaves–anything that would adulterate the chocolate" Doña Lupe dipped into the huge bag of cocoa beans and put them by handfuls into an harnero (strainer), sifting through them as she poured them through her fingers, shaking the strainer to get rid of any tiny impurities. She put the cleaned cocoa beans into a cazuela de barro (deep clay cooking vessel).

The large aluminum pot in the foreground holds ground cocoa beans that shortly will become a smooth, rich masa de cacao (sweetened chocolate for tablets).

Doña Lupe's chocolate kitchen, in the lower level of her home, is furnished with traditional petate (woven reed) mats for warmth, while the room where the costales of cacao beans are stored is kept cool to preserve the beans.

Doña Lupe grinds cocoa beans the old-fashioned way, using a metate and metapil, also known as a mano. A small fire (under the metate) keeps the metate and the cocoa beans hot during the grinding process.

The chocolate, ground smooth, rests in a wooden batea (shallow oval bowl).

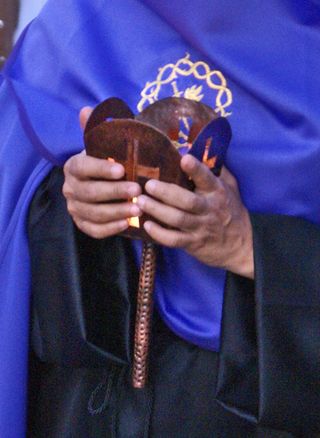

Doña Lupe uses a metal mold to form the sweetened soft chocolate into individual tablets. The top of the tablet of sweetened soft chocolate is scored into four quarters with the metal round to the left in the photograph.

The tablets air-dry in the warmth of the chocolate kitchen. The tablets that are scored in half are chocolate amargo: unsweetened chocolate. Both chocolate semiamargo (semisweet chocolate for making hot chocolate)) and chocolate amargo sell well.

When the chocolate is completely dry, Doña Lupe packages it in pink paper. A packet of sweet chocolate contains nine tablets. A packet of chocolate amargo contains seven.

She glues the label to the package and the chocolate is ready to sell.

This hand-embroidered tablecloth in Doña Lupe's dining room depicts cups and pots of hot chocolate, as well as the saying, "Chocolate Joaquinita, Industria Casera Desde 1898" (Cottage Industry since 1898).

Mexico Cooks! would love to know the proportions of chocolate, sugar, and cinnamon that Doña Lupe uses to make her chocolate tablets, but then she wouldn't have a secret recipe. We contented ourselves with buying a package of chocolate amargo (for baking) and a package of sweetened chocolate (for preparing hot chocolate). When you're in Pátzcuaro, be sure to stop in at Joaquinita Chocolate Supremo for your own supply of traditional chocolate.

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.