Archeologists generally consider the yácatas (pyramids with round bases) in Tzintzuntzan to have been a ceremonial center and residence for early Purépecha priests. Originally, on each of the yácatas was a temple made of wood in which the most important rites of the Purépecha people and government took place, including burials, of which about sixty have been found. The burials that have been excavated contain rich grave goods and are probably of kings and high priests. Although reconstruction began in the 1930s, two of the yácatas remain in their found condition. Photo courtesy Google Images.

The Purépecha make up the largest indigenous population of the state of Michoacán. Their ancient kingdom, centered in the town of Tzintzuntzan on the shores of Lake Pátzcuaro, is purported to have been an advanced and prosperous civilization as early as 900 A.D.

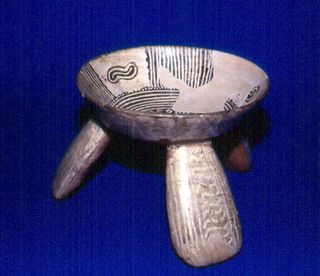

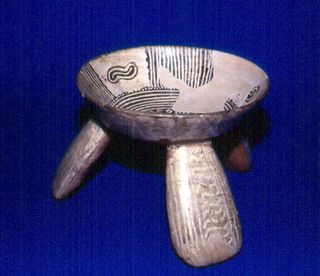

Archeologists discovered this very early tripod-form Purépecha vessel inside ceremonial rooms of the yácatas. Photo courtesy Famsi.org.

Less is known anthropologically about the historical antecedents of the Purépecha than about any other important Mexican group (the Olmecs, the Toltecs, and the Mexica, for example). The Purépecha had no written language and therefore kept no written record of their lives, culture, or activities. All of their history is extrapolated from post-conquest documents written by the Spanish. The Purépecha language was established long before the arrival of the Spanish and is in no way related to any other indigenous language of Mexico or any language anywhere.

In the early 1500s, the Lake Pátzcuaro basin had a population between 60,000 and 100,000 inhabitants spread among 91 separate settlements ranging over 25,000 square miles. Purépecha government was necessarily strong, with effective social, economic, and administrative structure. A strong religion with many gods and goddesses underlay and supported the society.

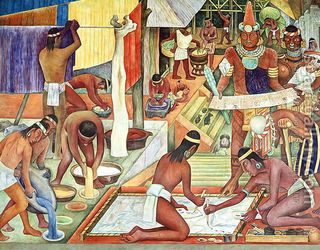

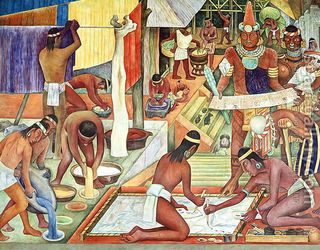

Tarascan (Purépecha) civilization. Detail of mural, Diego Rivera, 1942.

What happened to the Purépecha and their strong kingdom?

On February 23, 1521, the first Spanish soldier appeared on the borders of Michoacán. Even before this, however, the effects of the first contact had begun to be felt among the Purépecha. The previous year, a slave infected with smallpox had come ashore after crossing the Atlantic Ocean with the army of Spanish explorer Pánfilo de Naraváez and had triggered a widespread and disastrous smallpox epidemic among indigenous peoples, none of whom had previously been exposed to this sort of illness.

Tzuiangua, the Purhépecha calzonci (king) died in the smallpox epidemic of 1521. Measles and other diseases came along with the earliest Spaniards and led to further reductions in population. Partly as a result of these catastrophes, the young, newly-invested calzonci (king) Tzintzicha Tangaxoana chose to accept Spanish sovereignty when the first Spanish soldiers arrived, rather than suffer the fate of Tenochtitlán, the grand Aztec pyramid city located near present-day Mexico City. As evidence of his submission, he accepted baptism and brought Franciscan missionaries into the region under his protection.

It is unclear whether Tangaxhuan II, the new young king, failed to fully understand the Spaniards' intentions and how their system worked, whether he thought he could pull the proverbial wool over their eyes, whether he was poorly advised, or some combination of the three.

Torture and death of the last Purépecha king. Detail of mural titled "La Historia de Michoacán", painted in 1941-42 by Juan O'Gorman on the back wall of the Biblioteca Gertrudis Bocanegra, Pátzcuaro, Michoacán.

The Spanish had intended to allow Tangaxhuan II to keep some symbolic measure of autonomy for himself and his empire as a reward for his cooperation. However, when the Spanish discovered that he was continuing to receive tribute from his subjects, they had him executed. On February 14, 1530, the last native king of the Purépecha was put to death at the hands of the conquerers.

So begins the mystical creation history of the Purépecha people and Lake Pátzcuaro, the center of their spirituality. Still numerous and active in the modern world, the Purépecha maintain much of their supernatural culture in spite of the intrusion of globalization and the present-day world. The mid-20th Century Mexican-Irish muralist Juan O'Gorman painted the history of the Purépecha nation in the Pátzcuaro public library. The mural, a detail of which is shown above, depicts O'Gorman's vision of pre- and post-Conquest Purépecha life.

Don Vasco de Quiroga and a Purépecha woman, carved in cantera (a volcanic stone) and crowned with flowers. Outside the huatápera in Santa Fe de la Laguna, where Tata Vasco, as he is lovingly called to this day, founded the first hospital (house for shelter and relief) in Michoacán.

In 1533, Don Vasco de Quiroga, a Spanish aristocrat, was installed as the first bishop of the province of Michoacán. At that time, the province was much larger than the present-day state. Don Vasco governed an area that encompassed over 27,000 square miles and 1.5 million people. Don Vasco oversaw the construction of three Spanish-style pueblos (towns), each of which included a hospital, as well as the great cathedral of Santa Ana in Morelia, numerous churches and schools, and founded the Colegio de San Nicolás Obispo (College of St. Nicholas the Bishop), the first school in all of the Americas. Quiroga is immensely important not only to the history of Michoacán but also specifically to the Purépecha nation.

In The Christianization of the Purépecha by Bernardino Verastique (pp. 92-109), the author states that the primary task assigned to Quiroga was to "rectify the disorder in which Nino de Guzmán had left the province after the assassination of the cazonci." Unlike Guzmán, who was a viciously murderous and enslaving conqueror, Quiroga was largely benevolent. He assumed a pastoral role of protector, spiritual father, judge, and confessional physician to the Purépecha.

Tata Vasco teaching the Purépecha the Utopian ideas he held dear. Detail of Juan O'Gorman mural, "La Historia de Michoacán".

St. John the Baptist, fashioned as a Purépecha man. He's wearing his woolen jorongo (like a poncho) and his huetameño (straw hat from Huetamo, Michoacán). This early statue, so tender and so beautiful, so tattered and beloved, is hiding in plain sight in a one-room chapel just off the plaza in Santa Fe de la Laguna. His gentle demeanor melted my companion's heart and mine as well.

Tata Vasco organized the Purépecha villages into groups modeled on Thomas More's Utopia and thus extended his territorial jurisdiction. His actions brought him into direct conflict with the Spanish encomenderos (land grant holders). Quiroga recognized that Christianizing the Purépecha depended upon preserving their language and understanding their world view. He promulgated a multicultural, visual, and multilingual access to Christianity.

Even the Purépecha nation's name is debatable. Erroneously called Tarascans since the Spanish conquest, in the last 40-50 years the Purépecha have begun to reclaim their original name. The term 'tarasco' means brother-in-law in the Purépecha language. The newly arrived Spanish took Purépecha women, heard the Purépecha men use term 'tarasco' to ironically refer to themselves, and mistakenly believed that it was the name of the entire nation.

Descendants of the Purépecha remain in Michoacán, particularly in the Lake Pátzcuaro area. The language is still spoken, and many children speak Purépecha as their first language. During the last 50 years, a written Purépecha language has been devised and is used in a regional newspaper and in books.

Olive trees in what is now the atrium of the Templo de Sta. Ana, the oldest Catholic church in Michoacán. These trees were planted by the Spanish in the mid-1500s.

Olive trees planted by the Spanish conquerers nearly 500 years ago still thrive in the churchyard at Tzintzuntzan, the former capital of the Purépecha kingdom, on the shore of Lake Pátzcuaro. Some of the trees measure nearly 15 feet in diameter. Nearby, Purépecha descendants still produce the crafts of the old days: wood carving, pottery making, and tule (a kind of lake reed) weaving. The present-day town has a population of less than one-tenth of the Purépecha capital at the height of its power, and it continues to lose many of its young people as they migrate in search of jobs to other Mexican cities and to the United States.

Purépecha woman selling deliciously edible flor de calabaza (squash flowers), near Paracho, Michoacán. Photo copyright Mexico Cooks!.

Anthropologists are of two minds concerning contemporary Purépecha life. One group, the 'Hispanists', argues that the Purépecha remnant has become primarily a Spanish-speaking Mexican peasant culture. Though they have maintained their language and some of their basic Mesoamerican cultural elements (in particular their diet of beans, squash, chiles, and corn), they have become Hispanicized with regard to their religious lives, their economy, and their forms of traditional or 'folk' knowledge. In contrast, the other group is more persuaded by the consistencies they see between traditional Mesoamerican culture and the modern-day life of the remaining Purépecha. They note in particular the areas of relationship between language and culture, gender relations, socialization, and world view.

Next week: a look at Michoacán's Purépecha communities in the 21st century. Come with us!

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.