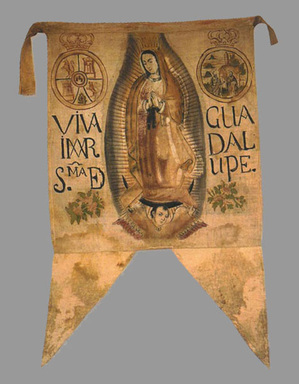

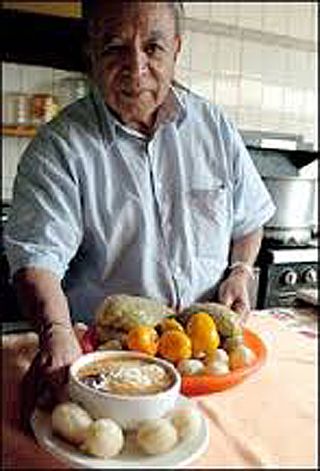

Daniel Ovadía of Restaurante Nudo Negro, Mexico City. Photo courtesy Chilango.com.

During the last 10 years, Daniel Ovadía has ranked among the wunderkind of Mexico City's restaurants. Barely in his middle 30s, he has already been at the helm of more than one kitchen: initially, he and a couple of friends opened El Changarrito, which closed for financial reasons. In 2005, cocinero (cook; he doesn't claim to be a trained chef) Daniel opened award-winning Paxia, which Mexico City received to grand acclaim but which closed without explanation in 2013. Several of his restaurants have come and gone, while others continue to exist. Among the latter are the neighborhood versions of Peltre, which Ovadía defines as a lonchería (a casual and inexpensive eatery, serving good fast food).

At the dawn of 2015, Daniel Ovadía and Salvador Orozco, his restaurant partner since 2011, opened Nudo Negro (the name means 'black knot') in Mexico City's Roma Norte neighborhood. The hype about the restaurant proclaims that it's unlike any other, that Mexico City has never seen a restaurant like it, and that the fusion of Mexican ingredients with touches of China, Vietnam, Japan, Thailand, and Venezuela make for unique dishes arriving at your table.

A couple of weeks ago, a friend visited me here in Mexico City. She's extraordinarily knowledgeable about the cuisines of parts of China, Vietnam, Japan, Indonesia, and Thailand, and has ordered and eaten well in all of those countries. For a few years, I worked in New York as a Chinese chef and also have a good understanding of Vietnamese cuisine. Neither of us claims any expertise in Venezuelan cooking.

Both my friend and I love food, with its many possibilities to delight and entertain the palate. We spend a lot of time talking about food, talking about ingredients, investigating cuisines other than the familiar, and trying new foods. She adores regional Mexican food and is a lover of adventurous food; I'm always interested in trying just about anything at least once. We don't mind eating more than we normally might at a meal together that's meant to be special for both of us.

During her recent stay in Mexico City, we happily ate at street stands, at a municipal food market counter, and at restaurants ranging from delicious pozole at La Casa de Toño to a close to perfect comida (Mexico's main meal of the day) at Fonda Fina.

After researching how and what we wanted to eat on her last night in the city, we discarded a number of excellent possibilities in favor of enjoying a cena (late evening supper) at Nudo Negro. The menu intrigued us, the food sounded both delicious and fun, and friends who had recently eaten there said they had enjoyed their experience. Result: reservation confirmed. We felt the excitement of an upcoming WOW!

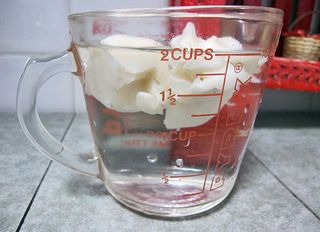

When we arrived, our waiter mentioned that our first stop would be upstairs in the kitchen, where we were greeted by the cooks and pinches (prep cooks) with an exuberant chorus of BUENAS NOCHES. A delightful young woman prepared two starter gorditas (little fat corn masa disks) of chicharrón prensado de pato with an adobo of chile ancho flavored with cinnamon, crumbled queso canasto, crema del rancho, and a good-sized blob of sriracha chile sauce (photo above). The savory gordita crunched, the sweet adobo was an interesting if unexpected foil, the dairy was creamy, and the sriracha tried its spicy best to bring the dish together. Eating standing up in the kitchen felt like an odd restaurant quirk, but we spooned up our gorditas and dutifully trod the stairs back to the main floor and our table.

Once we were seated, several waiters in turn talked with us about the menu (I had the Spanish version, my friend had the English version). We each ordered a cocktail from the extensive drinks list, which features classic alcoholic beverages in chronological order of their invention, plus several pages of artisanal beers. I asked for a mojito and my companion requested a Bloody Mary. My mojito was fine, if a little sweeter than they usually are. My friend's Bloody Mary was salty enough to raise her eyebrows and mine, and over-Worcestershired to the point of being undrinkable. Who sends a beverage back to the bar? We asked that hers be remade. Our antennae went up, but not up far enough.

As we discussed our preferences for other courses, we realized that our menus had some discrepancies: a dish appearing on my Spanish version didn't appear on her English menu, and vice versa. We soon realized that my menu bore the current date, while hers was dated May 2016. The waiter said that could not possibly be the case, but when he looked closely at her menu, he saw that it was indeed true. No staff member mentioned that the menu changed frequently, nor did we the clients know.

Nudo Negro recommends that dishes be shared; the two of us usually order plates to divide between us so that we can both taste as many things as possible, which made that recommendation easy for us. Ramen with matzo balls, our selection to start our dinner, comes highly touted by friends and by the restaurant's website. My companion had eaten a similar dish in a Brooklyn restaurant and was eager to try the Mexico City version; it was the first thing we ordered.

We ordered the ramen, as shown below in a photo which was posted at an earlier date by an anonymous Nudo Negro client. Our serious staff/client troubles started immediately.

Ramen with matzo balls (the two beige sph

eres on the left-hand side of the bowl). Image courtesy Twitter.

This is the ramen we received: with chochoyotes (the dark brown spheres on the left side of the bowl), small corn masa (dough) balls with a finger indent. In this case, the chochoyotes were prepared with ground black beans mixed into the masa. When I explained to the waiter that this was not what we ordered, he insisted that it was. Then he insisted that these WERE matzo balls: "Sí, señora, esferas de masa." "Perdón, pero masa no–pedimos matzo." "Sí, señora, son de masa." Irritated by this snafu in communication, we eventually gave up; the pronunciation of the two words is apparently too similar to an ear not trained to differentiate between them.

The flavor of the broth was very weak, the chochoyotes were grainy and unpleasant and fried rather than being boiled as is the norm, and the ramen (in English, noodles) were all but inedible: flavorless, pasty to the point of clumping together both in the soup and in the mouth, and without the springy texture of true ramen. The egg was correctly prepared, but the waiter offered no condiments. A nori (dried seaweed) sheet decorated the bowl, but no dashi or shoyu or pickles came with the soup. We were seriously disappointed by not receiving what we ordered. Much later, it occurred to us that ramen with matzo balls must have been listed on my companion's May menu and was not listed on my July menu. But why didn't anyone on the wait staff tell us? Waiters hovered over our table the entire evening, in an attempt to make sure that, as the headwaiter said, "your experience is exactly as you want it." Ay ay ay–would that it had been.

We requested the ostiones a las brasas (an order of six oysters, spiced and cooked over coals), but were told the oysters were only available per single oyster on the tasting menu. The waiter told us that there weren't enough oysters to prepare an order of six to share. It seemed odd, but he was quite definite. Later, after we had ordered other appetizers, he came back and said he was wrong, there were no oysters at all.

In place of the oysters, we asked for dumplings de pato (duck) and ceviche verde.

The duck dumplings, prepared with kaffir lime, almond milk, hazelnut oil, flash-cooked green beans, seta mushrooms, and smoked chile, sounded (and looked) marvelous. The truth? They weren't. The duck filling was too dense and under-seasoned; the dumpling wrapper was extremely heavy and doughy, with texture more like an uncooked empanada. The green beans were perfectly cooked, but their crunch didn't really combine well with the leaden, dense dumplings; the too-slick setas added flavor, but didn't provide fusion, just another unrelated texture and taste. The sauce was thick to the point of gloppy and added nothing to the flavor profile of the dish. I believe that the sprinkle of red atop the sauce was the smoked chile, but it brought no hint of smoked chile to the dish.

The ceviche verde consisted of tiny bits of fish marinated with slivered red onion, fresh coconut and cucumber juices, coconut, and lemon. The toppings are flowers cut from coconut meat (exactly eleven on every bowlful, according to the waiter), and sprouts. Yes, it's pretty–but most of the flavors were lost in the acidic lemon juice.

We initially tried to order three main dishes: a fish of the day, chamorro (pork shank) glazed with honey and cardamom (with dill, salted carrots and beets and mashed potatoes included) as well as the spiced fried chicken with another interesting-sounding salad, but our waiter said that we had already ordered too much food and he refused to allow us to have the chicken.

Chamorro with carrots, beets, leeks, and dill. One of the wait staff brushed glaze onto the meat at the table, but did not offer extra glaze to use as we ate. The bit of mashed potatoes was dull and flavorless. Everything on the plate, including the meat, was stone cold at the time it was served.

This pesca del día a las brasas (unidentified fish of the day cooked over coals) had a small amount of "Thai curry with chile morita" spread over it. Chile morita, which has a pronounced smoky flavor, is a smaller cousin of chile chipotle. The tiny amount of sauce had no smoky taste, and the fish was drastically overcooked. The middle object on the plate is yaki onigiri, a grilled rice cake, which in this case was grilled to the point of being tough and difficult to cut. The salad on the left-hand side is listed on the menu as fennel bulbs with a Persian lime vinaigrette. Instead, this salad was made of limp lettuce and shredded onions with halved cherry tomatoes and black olives that seemed to have come from a can; the dressing, whatever ingredients it contained, was inedible. The entire dish looked like it had been held too long under a heat lamp in a cheap cafeteria.

During the course of our meal, tension between us as clients and various members of the wait staff was palpable. My friend and I were thoroughly puzzled and frustrated by Nudo Negro's food. We talked about the difficulties in our meal with the head waiter, with another waiter who seemed to be at that level, and with our server. It was extremely disappointing to see that Daniel Ovadía was sitting on the terrace with another group of clients, within easy view of our table. At no time did we see any of the wait staff approach him to let him know of our problems. At no time did he look our way or show any interest the dining room. When I finally did hand one of the waiters my card to give to him, he immediately came to greet me with a kiss and a hug and offered a handshake to my friend–but at no time did he ask either of us if we were enjoying our meal, if everything had been to our liking, nothing of the sort. It was as if he didn't care at all. He talked with me about a business aspect of his business (a new restaurant in the offing), but not about the most crucial part of any restaurateur's business: the dining pleasure of the client. After only a few minutes with us, he returned to the group on the terrace.

My friend and I were tired of and more than annoyed by the evening's incessant struggle to dine, neither of us wanted dessert, and we asked for the check. Rather than bring the check, one of the wait staff brought us a dessert, courtesy of the house: cheesecake baklava with ground nuts and a pretty egg-shaped serving of normally subtly flavored rose petal ice cream, plus smears of jamaica reduction meant to have the appearance of rose petals. The baklava was edible, but the ice cream fragrance and flavor mimicked exactly the extremely strong scent of one of Mexico's iconic soaps: Rosa Venus. We laughed and left it on the plate after a taste.

Our server brought the check in its folder, laid it on the table, and immediately took it away again. The head waiter came to the table and said, "There is no check. There is no check. We apologize for everything." It was definitely the right thing to do and we truly appreciated the gesture.

Two thumbs down, readers. This is a first for Mexico Cooks!.

Restaurante Nudo Negro

Calle Zacatecas 139

Between Calle Jalapa and Calle Tonalá

Colonia Roma Norte

Mexico City

011-52-5564-5281

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.