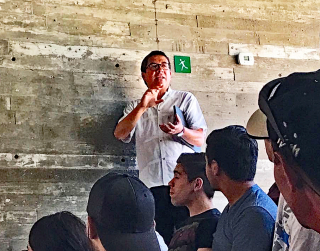

A perfect michelada, rimmed with Tajín and topped with crunchy fresh cucumber. Spicy, salty, beery, umami-rich, and completely refreshing.

Here in Mexico–everywhere in Mexico!–the single most popular beer drink is the michelada. Its ingredients, always based on beer, depend on the bartender, the part of the country one is in, or on one's personal taste. A michelada is an any-time, any-season drink.

We see fútbol (soccer) stadiums full of people slugging down liters of stadium-prepared micheladas, parties at home where no other alcoholic beverage is served, and restaurant tables full of people slurping them down along with their barbacoa, carne asada, or pozole–or accompanying a hamburger and fries, or a salad. The michelada goes with just about any sort of food. Popular wisdom also knows it as a super hangover cure, so hey–beer for breakfast in your hour of need? Why not, just this once?

The primary ingredient of any michelada is beer. Most people prefer a light-colored lager, but once in a while someone will order a michelada made with dark beer. Corona is just one option; any light-colored lager will do. First and foremost is to use the lager you prefer: Corona, Pacifico, Modelo, or any other. And your beer doesn't even have to be made in Mexico; use whatever country's beer you like best. Photo courtesy Corona.

The seasonings in a michelada typically include either Clamato, V8, or plain tomato juice, plus Worcestershire sauce, a very hot bottled salsa like Valentina, Cholula, Yucateca, or any of dozens on the grocer's shelf, salt—lots of salt—powdered chile, the umami-heavy seasoning liquid called Maggi, and freshly-squeezed jugo de limón (the juice of a key lime).

Rim a frosted pint mug or glass with powdered Tajín (a commercial mix of powdered dry chile, limón flavoring, and salt). You can find Tajín in almost any supermarket. There are imitators, but if you can find Tajín, it's the best. Photo courtesy Tajín.

Now add the rest of the ingredients. Here's a recipe to get you started; experiment with micheladas till the flavor blend is exactly the way you like it.

Micheladas a la mexicana

- light-colored lager beer of your choice

- Clamato or V8 or tomato juice

- 3 or 4 splashes hot sauce, more or less to taste. Try Valentina, or Cholula, or use your favorite.

- 2 splashes of Worcestershire sauce

- 2 splashes of Maggi sauce

- Juice of one lime

Fill the glass about ¼ to ? with the Clamato juice. Add the hot sauce, the lime juice, the Worcestershire sauce, and the soy sauce. If you used Tajín to salt the rim, pour any excess from the plate into the glass. Fill the rest with cold beer and top off your micheladas with sticks of celery or jícama, skewers of shrimp or olives, half-moons of cucumber, freshly-cooked octopus–really, anything within the limits of your imagination. And for good measure, add another splash of Maggi.

V8 juice contains a blend of reconstituted vegetable juices including tomatoes, carrots, celery, beets, parsley, lettuce, watercress, and spinach, plus a tiny percentage of salt, ascorbic acid, citric acid, and natural flavoring. Photo courtesy V8.

Campbell's tomato juice contains tomato juice from concentrate, potassium chloride, ascorbic acid, citric acid, salt, malic acid, and other flavorings. Photo courtesy Campbell's.

In the United States, the ingredients in Lea & Perrins Worcestershire sauce are: distilled white vinegar, molasses, sugar, water, salt, onions, anchovies, garlic, cloves, tamarind extract, natural flavorings, and chili pepper extract. Anchovies–did you know that? Photo courtesy Lee & Perrins.

Valentina is arguably Mexico's best-known bottled salsa. The photo shows the four liter bottle–nearly a gallon! That size should keep you in micheladas for quite a while. If you'd prefer a smaller bottle, you can buy Valentina, either hot or extra-hot, in a 12.5 ounce size. The ingredients are water, chile peppers, vinegar, salt, spices and sodium benzoate (as a preservative). The taste can be described as a citrus flavor, with a nicely spicy aftertaste. Photo courtesy Valentina.

If you're not already using Maggi for cooking, look for it until you find it for your micheladas. Of Swiss origin, Maggi is ubiquitous, literally a global phenomenon, used all over the world to add an extra touch of taste to savory recipes. It's indispensable in a michelada, bringing the utmost in umami to the drink. Your micheladas will be pale in flavor without it. Ingredients vary by country; if you have an MSG sensitivity, be sure to look for it in the ingredients list. Some countries' Maggi have it, some don't. Photo courtesy Maggi.

Finally, the taste of freshly squeezed jugo de limón (juice from the key lime) will brighten up your michelada in a way that regular lime juice won't. You'll find limones in many supermarkets and Latin specialty markets. The juice of one limón per liter of michelada is the ratio you want. Mexico Cooks! photo.

The name michelada is said to be made of three words: 'mi' (my) 'chela' (a popular nickname for any beer) and 'helada' (icy cold). How many micheladas are consumed in Mexico every year? Untold millions! Do your part to keep the numbers up!

Salud! (To your health!)

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.