This is just a portion of one gigantic calabaza de castilla (squash from Castilla), the winter squash that's used to make calabaza en tacha (squash cooked in syrup). Calabaza en tacha is a dish that's frequently seen on a Día de Muertos ofrenda (Day of the Dead altar).

The portion of squash in my photo (above) is about 18" in diameter; you probably will want to look for a smaller one in a Latin market near you. Right now, I'm seeing these squash in all the markets here in Mexico City, and it's the perfect cold-weather treat for your family. Even though the name of the squash suggests that it comes from Spain, it's Mexican in origin and is truly delicious in this recipe. Below the squash in the photo are beets, and behind the squash are plátanos machos (plantains).

Mari, the woman who at one time spoiled Mexico Cooks! by doing all of my housework, gave me a squash. She brought two home from her rancho (the family farm) out in the country, one for her family and one for me. The 8" diameter squash wasn't very big, as Mexican winter squash go, but it was plenty for me. Mari's first question, after I had happily accepted her gift, was whether or not I knew how to cook it. "Con piloncillo y canela, sí?" (With cones of brown sugar and cinnamon, right?)

The squash Mari gave me, next to a charming kneeling figurine dressed in ropa típica (typical dress) and selling typical green-glazed clay pottery from Michoacán. The figurine is made of cloth and is about 6" high; her wares are miniatures of the real thing.

Even though I knew how to spice the squash and knew how to cut it apart, knowing and doing these things turned out to be worlds apart. Faced with the project, I waffled and hesitated, intimidated by a large vegetable. The squash sat on the counter for several days, daring me to cook it before it molded. Then one of the cats toppled it over and rolled it around on the counter, so I moved the squash outside onto the terrace table and gathered my nerve.

On Sunday, I finally decided it was Cook the Squash Day. Mari was due to arrive early on Monday morning and it had to be done before she scolded me for letting it sit for so long. I chose pots, knives, and gathered the rest of the simple ingredients for a mise en place.

The squash with the first section cut out.

Cutting the squash in sections was the only difficult part of preparing it. The shell of the squash is hard. Hard. HARD. I was careful to keep the huge, sharp, carbon steel knife I was using pointed toward the wall, not toward my body. With the force I needed to cut the squash open, one slip of the knife could have meant instant and deep penetration of my innards. I felt really tough, knowing that I'd been able to cut it open with just a big knife and a few pointed words. (That's shorthand for 'I swore at it till the air turned blue above my counter').

The squash, cut into sections and ready for the pot. On the counter behind the squash is a 1930's Mexican covered cazuela (casserole), the top in the form of a turkey.

Once I had the (few pointed words) squash cut open, I scooped out the seeds and goop–many people just cook those along with the squash flesh–and cut it into sections more or less 4" long by 3" wide. I did not remove the hard shell, nor should you.

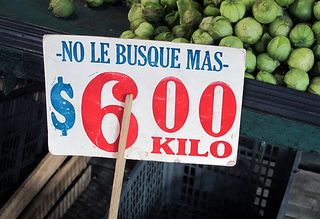

Piloncillo (raw brown sugar) cones in two sizes. The large one weighs 210 grams; the small one weighs 35 grams. I use the small ones in the recipe below. You'll also find these at your local Latin market.

Meantime, I had prepared the ingredients for the almíbar (thick syrup) that the squash would cook in. Mexican stick cinnamon, granulated sugar, and piloncillo (cones of brown sugar) went into a pot of water. I added a big pinch of salt, tied anise seed and cloves into a square of cheesecloth and tossed the little bundle into the water. The pot needed to simmer for at least three hours, until the syrup was thick and well-flavored.

Clockwise from left: Mexican stick cinnamon, anise seed, piloncillo, and cloves.

Several hours later (after the syrup thickened well), I added the pieces of squash to the pot. Cooking time for this very hard squash was approximately an hour and a half over a low-medium flame.

As the squash cooks in the syrup, it softens and takes on a very appetizing dark brown color. Calabaza en tacha is one of the most typically homey Mexican dishes for desayuno (breakfast) or cena (supper). Well heated and served in a bowl with hot milk and a little of its own syrup, the squash is both nutritious and filling.

Squash for breakfast! On Monday morning, Mexico Cooks! served up a bowl of squash with hot milk, along with a slice of pan relleno con chilacayote (bread filled with sweetened chilacayote squash paste) for Mari. Her first question was,"How did you get that squash cut open?" Mari laughed when I told her about my struggle, and then told me that her husband had cut their squash apart with a machete. Mari thought my squash came out almost–almost–as good as hers.

In the evening, a friend came over to have some of the squash for a late supper. HER first question was, of course, "How did you get that squash cut open?" After I told her, she told me that her mother takes a squash like mine up to the roof of their house and throws it down onto the patio to break it apart!

Calabaza en Tacha estilo Mexico Cooks!

Ingredients

One medium-size hard shell winter squash (about 8" high)

6 cups water

14 small or 2 large cones of dark piloncillo (Mexico's raw brown sugar)

2 cups granulated sugar

4 Mexican cinnamon sticks about 2.5" long

1 Tbsp anise seed

1 tsp cloves

Preparation

Heat the water in a large pot. Add the piloncillo, the granulated sugar, and the cinnamon sticks. Tie the anise seed and the cloves into a cheesecloth square and add it to the pot. Cook over a slow flame until the liquid is thick and syrupy, approximately three hours.

While the syrup is cooking, prepare the squash. Cut it into serving-size pieces as described above. If the squash shell is very hard, take adequate precautions so that you do not hurt yourself as you cut it in sections. You can always throw it from your second-floor window onto the patio!

Add the squash pieces to the thickened syrup and simmer until the squash is soft and takes on a deep brown color. Cool for 15 minutes or so before serving. Re-heat for desayuno (breakfast) or cena (supper). Serve with hot or cold milk poured over it.

Makes about 16 servings.

¡Provecho!

Looking for a tailored-to-your-interests specialized tour in Mexico? Click here: Tours.