Photo courtesy of Susan Nash Fekety.

Photo courtesy of Susan Nash Fekety.

Glorious springtime jacarandas convert Morelia, Michoacán, into something close to heaven.

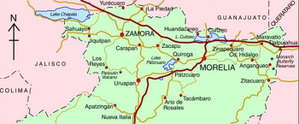

Those of you who have been reading Mexico Cooks! for the past few months know that I am a big fan of the state of Michoacán, the state that wraps around the eastern and southern borders of my own state of Jalisco.

I’ve written several articles about the wonderful attractions in Michoacán. In addition to enjoying the annual events depicted in those articles, it’s great spending any weekend of the year there, enjoying the ambience in the mountains around Pátzcuaro. It’s all so completely different from my life in Guadalajara. It’s an easy four-hour drive to Pátzcuaro on the cuota (toll road); the libre (free road) takes just a bit longer but is beautiful and well worth the extra time.

Last January, three friends visiting me from different parts of the United States (Alan, Jeanne, and Sara) and I jumped into my new car for a weekend in Michoacán. We’d decided this would be a great chance to see several of the towns and villages near Pátzcuaro, especially a few towns which are centers for making certain specific crafts.

Our first stop was for lunch—of course! I wanted to introduce my newly arrived friends to one of my favorite haunts along the libre (free highway), just to the west of Zamora. The restaurant is always packed with people enjoying the specialty of the house: carnitas, a heavenly platter of tender, juicy, deep fried pork meat. We ordered a kilo (about two pounds) to share. Our carnitas came heaped up on a platter and seemed like much too much to eat, but we polished it off, along with freshly made hot tortillas and several wonderful made-in-the-house salsas.

After lunch, we were back in the car for the next leg of the trip. Two hours later, we were checking into our hotel on Pátzcuaro’s small plaza. We made an early night of it after making plans to spend the next day investigating local crafts.

Tzintzuntzan

The next morning we headed for Tzintzuntzan, just outside Pátzcuaro on the road to Morelia. Tzintzuntzan means ‘the place of the hummingbird’ in the Purhépecha language, and if you’ve ever heard a hummingbird protecting its territory from other birds or from cats, you’ve heard the onomatopoeic sound. The town is small, charming, and filled with fascinating things to do and see.

Our first stop was the town artisans market. The market is on the left hand side of the main street through town—you can’t miss it. Alan was looking for a tall clay pot for cooking beans; once the unglazed terracotta pot is cured using salt and boiling water, the clay imparts its special flavor to the boiling beans. Jeanne wanted a clay comal (round griddle) for making tortillas and quesadillas. Sara got caught up looking at the locally hand-produced straw and wood items and was especially fascinated with the wooden molinillos (hot chocolate beaters). These beaters are carved from one solid block of wood into marvelous utilitarian designs just right for whipping hot chocolate in a cup or pitcher. To make hot chocolate, milk or water (or a combination of the two) is heated to almost boiling, a tablet of Mexican chocolate is dropped into the cup or pitcher and allowed to melt a bit, and then the molinillo is spun between your hands to froth and mix the chocolate with the liquid.

Alan did find just the right bean pot among the hundreds of pots for sale in Tzintzuntzan’s artisans market. His face beamed as he stowed the fragile pot in my trunk. Jeanne looked at every comal she could find but finally decided that the thin clay griddles would never make the trip back to Kansas City intact. She bought some straw Christmas ornaments instead. Sara bought seven molinillos, one for herself, one for each of her five nieces and one for a co-worker. I was the cheerleader, urging them to get what they wanted and not wait till later—these crafts, inexpensive in Tzintzuntzan, can cost up to three times the price in Guadalajara.

We took time to visit Tzintzuntzan’s two churches, an easy walk since both are in the same enormous courtyard. Although we wanted to visit the church offices, they’re currently closed for conservation of their beautiful 18th Century frescoes.

Alan, Jeanne, and Sara took picture after picture of the ancient olive trees in the church garden. Local legend says that these huge olive trees—some measuring as much as fifteen feet in diameter—were planted by the Spaniards in early colonial days. Many of the tree trunks are hollow in the center and their gray bark is gnarled with age, but their branches continue to produce fresh green leaves every spring.

We chatted briefly with an art conservator who was working on restoration of a catechetical mural in the patio. He told us that the conservation effort was funded by the state, by INAH (the National Institute of Anthropology and History), and by a group of interested people in Mexico and that all of the conservators have come from the nation’s capital to work on the site.

Our next stop in Tzintzuntzan was on the road heading back toward Pátzcuaro. I was eager for my friends to see the yácatas, the Purhépecha pyramids built above the indigenous temple honoring Curicaveri, god of the sun fire. These pyramids were apparently built around 1200 AD, when the Purhépecha kingdom was the most powerful in Central Mexico. Today, the site has a small museum showing exhibits of pottery, personal items and jewelry that have been excavated in the immediate area.

Outside the museum, the flat land on which the yácatas stand is dense with huge trees. The pyramids are built of individual stones hewn from nearby quarries. The stones were chinked together in round-edged pyramid forms that still stand sentry over the ancient temple below. The scent of pine in the air, the view of Lake Pátzcuaro just to the northwest of the pyramids, and the mental images of long ago rituals make this site a magical place.

We left the yácatas to drive back to Pátzcuaro. Once on the road, I remembered that I had commissioned a lamp shade (a similar shade is at the far right center of the photo) in a village just off the Tzintzuntzan-Pátzcuaro road. We took a brief side trip to pick it up at the taller (design workshop). The woven reed figure in the foreground is a catrina. Later this year Mexico Cooks! will talk at length about this traditional folk art form and its origins.

Our next stop was lunch, at around two o’clock. This gang loved tasting the regional specialties prepared in the Zona Lacustre (Lake Pátzcuaro region) of Michoacán. Our midday meal, the main meal of the day in Mexico, consisted of Lake Pátzcuaro whitefish, Sopa Tarasca (a traditional bean-based soup with chiles, cream, and cheese), and other typical Purhépecha delicacies.

We spent the rest of the afternoon poking around in the many shops in Pátzcuaro, examining the fine crafts made all over the Lake Pátzcuaro region. Textiles, guitars, wood carvings, lacquer ware, and pottery of every kind—from full table settings to highly decorative ornamental pieces—fill every shop. It’s possible to buy items for a few cents, and it’s possible to buy items costing many hundreds of dollars. No matter what your budget, Pátzcuaro has something right for you.

Next week: In Part II of our Michoacán shopping spree, Mexico Cooks! visits Santa Clara del Cobre and yet another Michoacán market.

Leave a Reply